American Medical College Application Service

Interview with Incoming Stanford M1 Accepted

Hello Everyone!

As promised, here’s the confidential(identity) interview from the accepted Stanford student. They’ll be starting this year as a M1. As a nontraditional premed, switching majors several times before finally deciding to apply to medical school.

It’s interesting to note we both applied to Boston University and Stanford, however we both never received interview invitations from each other’s respective current medical school — it really goes to show there’s interpretation about what constitutes a good fit for their institution, and we found our own fit. For myself another interesting point of this person is that, like me, it took them many years to finish their college career — we both took multiple breaks for work and switched majors innumerable times before deciding on applying to medical school.

Anyways, I had to distill a nearly two hour conversation where we easily went into tangents (mostly entirely my fault). After laughing and removing the tangents, here is the more educational and likely useful results:

Q. 1. When did you decide that medicine was for you, and why?

Basically, I realized medicine could be a career for me because of the position it occupies in relation to other fields. As a community college student, I had the opportunity to take a wide variety of classes in different fields, without needing to prematurely declare a major. I had always been interested in fields where I thought I could make a difference, I dipped my toes in psychology, sociology, political science, “hard” sciences (thought about a PhD), public health, and even art (documentary photography). For me, medicine fits snugly between public health and the hard sciences, and gives me the best of both worlds (well, what I feel is the best of both worlds). Public health was hard for me because it was a bit far removed from the individual level, obviously since it’s more focused on populations. This is great of course! But that was hard for me to work with, because actually seeing change takes a LONG time, if you see it at all. Bench research is cool too, I still love it, but couldn’t see myself devoting my life to it because it was easy to get caught up in the little things, without the human perspective, and I felt a little lost there, honestly. Medicine allows me to inform both fields with a clinical perspective, work with both fields as part of the health team, and still enjoy what I do

Q. So, do you think being a nontraditional gave you a different point of view? For example while studying.

I think so. I can’t say that more traditional premeds didn’t learn the same things I did, but I can say that I wouldn’t have the perspective I do without doing it my way. Having studied a variety of topics, I kind of felt that medicine was just one career path that could be taken. It fits a small niche in between all the other things people can do with their lives, or to help others. Plus, being nontraditional, working through school, all of that…I had to learn to prioritize and really figure out WHY I needed to do some of these things. I think premeds often get caught up in “the list”, the list of shit we’re supposed to do to be competitive. And a lot of us end up with huge resumes of shit we did that had no impact on us or our communities

The end goal is to be a great doctor…so these experiences should be towards that goal. Activities aren’t just there for filler. Med schools look for these activities because they think we have something to learn from them. And as a nontraditional student, I think I may have had an easier time figuring that out

Q. Lately, schools have really been pushing for diversity, how do/will you bring diversity to your program?

As for the diversity question…I STILL have trouble answering it. I think it’s because there’s no single factor that stands out as HI THERE DIVERSITY. I’ve mentioned before that I am certain that all of us are really diverse. We have our collections of scores and activities on the applications that look the same in bullet-point form, but different students get into different schools. In any case, I think being a nontraditional premed has given me some interesting opportunities. I took extra time in school; it took me eight years to finish up my degree, so I was able to explore a number of different areas of study and work part-time throughout undergrad. After all of that…I can’t help but see medicine as integrated with every other field, and my approach to healthcare in general requires that we don’t separate “health” from the rest of our patient’s lives. I also had time to make big commitments to projects that I cared about, and learned more than I could have imagined. I helped get a nonprofit global health organization started, which taught me as much about public health as it did about team work, leadership, and resource management. I worked in a research lab for a few years doing more engineering-based health projects, and was inspired by the potential future of stem-cell based diagnostic devices and therapies. I think the biggest opportunity I had while being nontrad, and perhaps bringing some diversity to the mix is my restaurant work history. I got my first job at 16 working in a cafe and bakery, and from there moved on to other cafes and finally ended up serving and bar-tending at a restaurant as I got older. It seems like working during undergrad isn’t typical for a lot of premeds, so I’m so glad I had a chance to do it. Of course, I hated it at the time and it was stressful, but being forced to talk to strangers day in and day out will probably help my bedside manner more than any amount of shadowing doctors could do. I learned a lot about making people feel comfortable and responding appropriately to misplaced anger by waiting tables. Although it isn’t directly related to medicine, waiting tables taught me a lot about professional communication in strained situations. People can get really upset about their food, it seems! Or parking, or having to wait for a table…about a lot of things outside my control. And I feel that happens in everyday medical practice often, so having a little bit of experience managing those situations will likely help me in the future. Waiting tables was also a great teamwork exercise; you really can’t survive the floor without working together, even if you don’t always get along with your coworkers. Maybe that gives me some of that coveted diversity? Who knows, I think it’s the summation of our experiences that gives all of us a unique perspective.

Q. So, as a nontraditional or traditional premeds was there anyone who mentored you? Also, applying to medschool is pretty nebulous; have any guidance or tips along the way?

I’m lucky to have had a great mentor in this whole thing. I think as you’ve pointed out a few times, there are a lot of people who are just waiting for us to fail, to not make it. So, I had my mom, who is a doctor and a teacher. When I have questions about how to be a great doctor, I always turn to her. For the premed-y things though, I kind of just went with it. Internet-searching. Berkeley doesn’t have official premed advisors, so I kind of went at it based on anecdotes from friends and the internet

As for my tips…I think the best ones I have are to do what you love…pick a few key activities that will help define and shape you, and give them your all. Don’t mess around with 100+ random activities that you only contribute 10 hours to.

Also, keep a journal of everything. Not only does it make it so much easier to learn from and reflect on your experiences, but you will thank yourself SO MUCH when applications roll around.

And surround yourself with good people, even if they’re not premed or doing the same things you are. Don’t let negative folks discourage you, don’t take SDN too damn seriously, and don’t put other people down because we never know where they’ve been

Regarding the question of, “For premeds without a committee or reliable advisors do you have any tips?” that’s a hard one. Reliable information is difficult to come by, and you don’t want to get sucked into the anecdotes too much, because they may be wrong! I think some of the books out there are pretty good –the ones written by previous admissions officers. I guess my major tip for anyone is just always frame your activities or potential activities by thinking “How will this make me a better doctor? What am I learning or contributing?” If you can come up with solid answers to that, then it’s a worthwhile activity lol.

And the usual: don’t let your GPA slide, set study schedules to keep it up, check school websites to meet prereqs, and don’t think the MCAT will be a breeze.

Q. I suppose you should probably jot down that answer [from the journal etc.] as well for later during secondary/interviews?

- YES, absolutely. Take notes, always. Makes life so much easier down the line when time is of the essence. I was lucky that I had some notes and journals, but I WISH i had an updated CV.

- Oh…another pro tip. Start saving a lot of money — like yesterday. Charging app fees to your credit card is awful (that was me, it sucked).

Q. As you already know, I don’t report MCAT scores; but, you did very well, do you have any study tips?

Well, since everyone studies a bit differently, it’s kind of a hard thing to say for sure. The one thing that I think will work for everyone is to set a study schedule. Like map out every single day, what you’re going to review, how many problems you’re doing to try, etc. Even map out your break days

- I also tend to think that you shouldn’t review all of one area, then the next. Should probably do one chapter of physics, one chem, one orgo, one bio, then repeat with the next chapters

- Practice problems are golden, obviously. do as many as possible, but I think it’s best if you don’t re-do the same ones. I saved all my AAMC practice exams for the last month

- Flashcards are great for random facts, and can be taken anywhere for quick review (on the bus, between classes, etc)

- Always focus on understanding and connecting concepts, rather than memorizing shit

*Doctoorbust: a caveat, remember pick tips that work for you, ignore any that don’t.

Q. I know you’re tired of hearing this but, any idea what you’re going to specialize in?

Not a clue! I’m trying to go into it with an open mind, simply because I know I haven’t seen even half of what specialties are out there. Even for the ones I have “seen”…it’s difficult to know if my experience in them as a premed was anything like the way they actually are. So, I’m trying to be open.

Plus, it’s hard to know where the field will be in 4-5 years. Things change. The structure of medical practice is undergoing some pretty significant changes, and I’m not really sure where it will all end up.

Q. How do you feel about the coming changes (healthcare)? There’s a lot of anxiety in some groups about it.

I honestly don’t know. I see it as a good thing, a step in the right direction for expanding patient coverage, but I can also understand the concerns from a doctor’s point of view, as far as who is getting reimbursed for what, and additional constraints on their time I think it is easy for us to say, as folks who have yet to enter the medical field for real, that expanding coverage is GREAT and it’s easy and things like that. But I’m not sure we really know what it’s like in the trenches. I’m thinking specifically of primary care, it seems that it’s going downhill fast for those currently in family practice and internal medicine.

For the record, my personal opinion is that expanding coverage equates to awesome. But I don’t think we can neglect the concerns that have been brought to the table by our colleagues, either.

Q. What are some things you wish you did as a premed now that you’re going into medschool?

I wish I had traveled more, and taken more time for non-premed activities. I definitely enjoyed all the work I did in preparation for becoming a doctor, but I let some things slip too

I would just advise people to always make time for hobbies, for themselves. This is because hobbies are every bit as important as engaging in research or volunteering. Being healthy and happy will make you a better doctor, too.

Maintain relationships! Friends, family, don’t let it slide because you’re too busy studying.

Q. Now, you’ve been there and done that. What are some misinformation points you’ve heard about being a premed or applying that you believe to be false, at least from your experience?

The biggest thing I think is that you need a perfect GPA and perfect MCAT score, or that having X hours of these activities are all it takes. Or that it’s guaranteed to get in if you have those things. And you see this everywhere. “My friend has a 4.0 and a 42 MCAT and thousands of hours of volunteering and research and didn’t get in” or the other commonly seen thing “I need a 4.0 and a 42 etc in order to have a shot.”

Yes, you need decent numbers, but that will only get you so far. We have to learn from our experiences in order for them to count. The hours spent doing an activity are usually correlated with learning and reflecting, but the hours themselves don’t mean anything

The other thing about applying that I saw a lot is the obsession with school rank and the numbers. It’s not all a numbers game. Schools have different missions, different focus points that they look for in their applicants

The smart applicant will choose schools that they will fit into, whose goals are in line with the applicant’s, or the applicant feels he/she can contribute to

The process feels like a crapshoot. To some extent, it probably is, but that doesn’t mean that applicants can’t maximize their chances. Obsessing over numbers won’t get you anywhere. and the thing is, just because your experiences don’t fit into one school doesn’t mean they don’t fit somewhere else. For instance, I was rejected outright from BU! But I got in somewhere. And you got into BU! And were rejected from other places we all have different strengths, just have to play to them. it takes some serious self-reflection and honesty on the applicant’s part. Still, no one’s saying it’s not competitive. But…always remember the numbers aren’t everything. My GPA sucked, and I got in somewhere.

–end–

Thanks for reading! I’ll try to keep posting while moving!

AMCAS II Ex. 5 — What’s Your Weakness?

We are all full of weakness and errors; let us mutually pardon each other our follies – it is the first law of nature — Voltaire

During the secondary applications, there is a good likely hood that you’ll eventually hit a question that asks for your to explain your weaknesses — some questions may even have you elaborate more, some less. As premeds we’re hyper vigilant when it comes to addressing our weaknesses. The worst thing you can do on this essay is to wall yourself up, become defensive, and start playing “cat and mouse” on this question. When interviewed, this is a question interviews like to toss in, so the better you know this question the better you’ll be during it. In fact, there’s seldom a job interview that I’ve had that also didn’t ask this question (at least a job that preferred a degree).

On the other hand you may indeed be perfect, good luck explaining that to your interviews who likely can easily give you a running list of their “weaknesses”.

Here was my strategy in answering the question:

1. Present weakness (feint)

The first step to many problems is to first acknowledge you have one. (see step 3). In my example it’s my “self doubt” about past decisions.

2. Rationalize/humanize, but don’t minimize weakness (parry into step 3)

Use an explanation to explain what your weakness is in context, then project how this could be a ‘problem’ later. Pretty much, in this phase I was beating my reviewer to the punch by acknowledging my issues, then being realistic about how that is a weakness in their context as well. After that, I used that to transition into the next step, step 3. In my case I tried to reason with physicians who probably were just as neurotic as I was about things, so it wasn’t a hard argument to bridge rumination and self destruction.

3. Propose solution/plan of action for your weakness (Parry into a gentle counter attack ‘riposte’)

Up until this point, I was on the defensive as a writer, but at the conclusion I moved towards the offensive, I decided to address how I’d overcome my problem: becoming more systematic, learning how to trust and delegate better (more trust in the process less restless nights in theory). This helped turn my weakness into more of an, “Aha!”, moment then a guilty admission. The key here is to really give the “how will you solve” this problem prompt real consideration.

And the golden rule — don’t BS ( unless you believe the BS too, but that’s some type of Inception type concept that we don’t have time to cover).

—Start–

What is your weakness?

I feel one of my largest flaws is my tendency to ruminate on my past decisions. As a future doctor I could imagine myself always wondering if I could have provided a better outcome for a patient: if I just had noticed a symptom sooner, prescribed medicines more or less aggressively, if I made the correct ethical choice, and wondering constantly if there was a better way to perform my duty. This year I have strove to empirically record my observations using an online journal; it has allowed for me reduce circular worries. Later, I could assuage my concerns with meticulous chart recording and recording case studies. I should also learn how to better develop trust and delegate to others, this would help reduce a lot of stress. These skills would transfer into medicine as I better learn to foster team work with other allied professionals. While I believe self-criticism is necessary, and should be invited, nonconstructive self-doubt helps no one.

–End–

As you may have imagined, to reflect on things is healthy but to ruefully regret is not a good thing. You may have also imagined that this trait would have made me more anxious during application season, at the beginning this was indeed true. However, during that time I grew to appreciate a new philosophy about my time and how much I would worry about things.

AMCAS II Ex. 2 — Diversity Question

di·ver·si·ty

diˈvərsitē,dī-/

noun

- What do you know about diversity?

- What is your understanding what diversity means in the current medical age?

- How do you tie that together into an argument of how you’ll help better that medical program?

- I found it difficult to brain story what makes me” diverse”. This is only natural, I speak English fluently as a native, but when someone asks me to say something “in English” I can’t think of a thing. So, instead I brainstormed the tangential answers by pretending I was addressing a future patient who misunderstood me, thinking I had nothing in common with them. I then tried to think how I’d assuage their concerns, then it was easier to shift gears into how writing about my “diversity”.

- Do not confuse this with the “hardship essay”, though your diversity may contain hardships that in fact make you diverse.

For my own diversity essay, I tried to take advantage of the changing medical landscape with the Affordable Health Care Act, allowing current events to segway into my understanding of diversity was easier for me (it almost gives you a skeleton to work around). Though, the caveat here is that you have to be up on your world and national news to play the part once you arrive at interviews (better start listening to Al Jazeera and NPR now). For myself, growing up without healthcare had an enormous impact on my quality of life, after all when you have a big family you have the unfortunate consequence of seeing ‘statistics’ play out as you’ll see in my diversity essay:

A physician must interact with patients across a large spectrum of income classes, a large swath of patients live in poverty. Therefore a doctor with a diversity of experiences may be better able to adapt to this fact. Lack of affordable health insurance inexplicably leads to overuse of emergency rooms, I know first-hand as I wasn’t privy to having a primary physician as an asthmatic who couldn’t afford insurance. I can only imagine that with the passage of the Affordable Health Care Act the diversity of patients seeking treatment can only increase. Being one of *14 (two dead) I’ve seen that diversity first hand having: a brother diagnosed with HIV, one dying after chronic cocaine abuse, and a brother currently in prison. To better get to know a diverse population I have spent time working with myriad of individuals from prison as a mentor, lecturer and tutor. As a volunteer in children’s oncology department I learned that compassion is a component of professionalism. Furthermore, I am gaining a greater understand the research process as an IRB/ACUC member. As an IRB member and Ethical Compliance Officer I weigh risk versus beneficence in order to protect special populations (prisoners, children, mentally disabled, and pregnant woman) from dangers of irresponsible research: misleading informed consents, conflicts of interest, manipulation and undue influence. I believe my diverse background will create a solid foundation of experience as a medical student and practicing physician.

–end—

It’s likely that if you’ve gotten this far, you have a story to tell. So, be assertive and tell it.

*In case you’re curious, for myself, I currently no interest in children nor having a huge family. For now my houseplant named, Fernando, makes a good son.

A Year Has Passed Since I Applied to Medschool

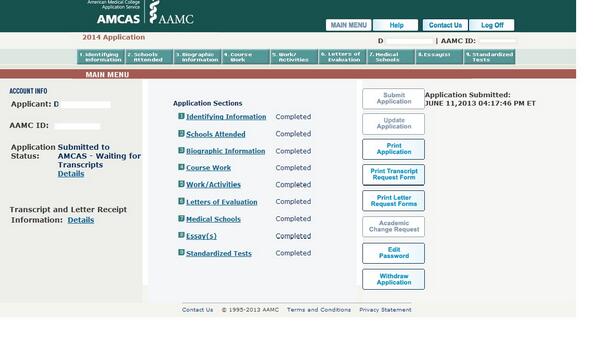

A year ago, on this day, I submitted my AMCAS. I held off on submitting to edit a few things, I think the effort & risks were worth it.

During that period I brushed the dust the cob webs off of my disused Twitter account, started blogging, and tried to keep myself occupied. I do better under stress if preoccupied. I then tried to report to you all about what I’ve empirically learned during the application process, being sure to only post about things after I had experienced it. As you may recall, the point of this blog is to record my process from premed to medical school. My first day of school is on August 4th, and I’ll be relocating to Boston permanently on July 30th. I’m pretty excited to meet my classmates!

A year later, I’m still learning my way around Twitter, still blogging, but this time I’m also in medical school. My problems last year are replaced by welcomed medstudent problems — though, it’s a problem I opted into!

Ready to Apply to Medical School?

Hello Everyone,

Are you applying for medical school this cycle? Nervous? It’s okay, I was here last year too, it worked out for me. Remember, once you press that submit button you’re in it to win it, so don’t look back now. My last second advice:

– Submit early, but don’t submit garbage. As much as I’ve been harping on you to apply early, it doesn’t make much of a difference between the first day and perhaps next week. The key here is: will your application be better by that time? If yes, then wait a few days to work things out. If no, and you’re just nervous, then it’s time to take the plunge and apply. Also, the MCAT and LOR can all be updated even after you submit, so if you’re waiting on these to submit then you’re making a big mistake. Even if you have a great MCAT score and award winning LORs, if you submit late in the season it’ll still take time to get verified plus there’s less seats for you; so, if you’re school has rolling admissions you’re chances have diminished significantly. The process of applying to medical school is NOTHING like most universities because of rolling admissions.

– If you didn’t opt for the $25 MSAR (potentially less than 1% of total medschool application bonanza) you’ll likely be very sorry later on. I was lucky, and I bought mine before I applied. If in the future you’re reading this, and its now secondary apps period and you still haven’t bought it, well you’re likely wishing you did — but don’t worry it’s still incredibly useful during the secondary and for prepping for interviews. If you feel like data mining all over the internet yourself, knock yourself out.

– Ignore most SDN hype, except for the “verification” threads. There are a series of threads you can search for using “verified” or “verification” as terms in SDN, you’ll see last years verification pattern. People will post the day they submitted and they day they were verified. I can save you a lot of time by saying it’ll take either exactly as long as the AMCAS told you or shorter unless you application is returned to you. You don’t need the extra drama at this point in your life. Don’t worry about when other people are receiving their secondary, invites, or rejections etc. For example, one school I interviewed out explicitly told us that they’ll be saving spots for other applicants they plan to invite later, some schools feel a little more cavalier about when they’ll contact you. Give schools some time to process things before you panic about how quickly they may be contacting you. When I put in my application at Boston University, I had already interviewed at other programs before I was even invited to an interview, so each school does their own thing. Pro tip: getting the MSAR will help you understand each schools’ deadline yourself.

– You’ll feel a large weight lift off your shoulders once you press the submit button. Awesome! Now, take a day off or two if you can muster it, and start working on secondary application drafts. The key here is to remember, no matter how well written your draft is, it’s still a draft and it can’t be submitted until you’ve customized it so much no one can tell you pre-wrote it. Here’s a secret, everyone reuses their secondaries to an extent, all schools know this. It’s really the only way to crank out 50-70 short essays in a month or two. But, humor medical schools by personalizing — each secondary should sound like they’re pretty much the only school you’d ever want to go to. And to be honest, by the time I wrote my secondary I actually felt emotionally bonded to each program. I actually got sort of depressed when I had to withdraw my acceptances, because I got so attached to each program, it felt like I was breaking up with someone I liked each time I withdrew. Everyone wants to feel you love only them after all. If your hearts not in the secondary than they’ll spot it, they have some type of clairvoyance about it.

– The secret to completing a good secondary is to love each school you apply to [while filing out their secondary] and staying organized. Part of that means doing your homework about applications. Schools are very generous about giving out their old secondary essays. Unfortunately, this doesn’t always mean that your school will provide it directly on their site — but a lot do if you just Google it. On SDN you can also search for past secondary prompts. The key is for you to realize that there’s really only a handful of categories that they’ll ask you about, so once you have good ideas developed for multiple topics you’ll be fine. I’ll spend more time talking about secondary applications soon, for now this older article I wrote should help:

https://doctororbust.wordpress.com/2014/04/17/secondary-the-mill/

– Don’t be afraid to ask for help, or even reputable companies/accounts (ProMEDeusLLC, MedMentors, Accepted, MDAdmit). People like to brag about how independently they applied to medical school and were fine. But, with all do respect, this isn’t a “lifting contest”. In the end only one thing is going to matter when the dust settles: are you in medical school or are you at least closer to it for the next cycle. I was one of those people who did so pretty independently: no premed advising, no tutoring (although I was a tutor later), self-studied for the MCAT (Examkrackers), and I personally didn’t use advising services during the AMCAS. But you know who’s going to care about all of that in medical school? No one. Do what you have to do, don’t under utilize your resources. I dodged a bullet, feel free to reach out for help and advice.

– A rejection nor an acceptance dictates your value. Everyone receives rejections, and some will get both rejections and acceptance(s). It seems almost like a character building exercise, you could probably win the Noble Peace Prize, single handed cure Malaria, and resurrect the dinosaurs and you’d still probably receive at least one rejection. The point is, using my culture as a reference point for this example, that you probably won’t marry anyone if you don’t at least date someone. You have to be willing to stumble, roll down a hill of jagged rocks, and then spring up and say you’re ready for more! Getting an acceptance is also pretty awesome, but this doesn’t mean that person is necessarily more qualified — after all everyone applies so different that while the scores matter, it’s hard to objectively rank application versus application.

– Work on your weak points now. If you’re not sure you can vocalize “why medicine” and “where do you see yourself in 10 years after attending this program”, then get that hammered out now. If you’re heads in the sand about the Affordable Health Care act, you better get up on your game. If you’re not used to defending your opinion in front of someone you think is “superior” to you, then you’d best learn how to do that now as well prior to interviewing. If you’re still in college there are probably programs to practice interviewing available to you. It’s also easy to find typical interview questions if you search online. Print them out, and have someone ask you. I ignored my own advice on this one, I yap all the time and argue with professors and sometimes a physician or two so I just went into my interviews mostly cold because I felt comfortable. My interviews, it probably felt more like I was interviewing them at times, and I was. Also, for me, I get more nervous if I put too much prep time into talking — go figure. So, do what works for you, but at least practice a bit in whatever way works for you.

That’s all for now!

Awaiting Financial Aid for Medschool

Hi Everyone!

As you probably already know, I applied for medical school last year, interviewed and was accepted. I will be starting in August — white coat ceremony is on day 1 of school!

If you’re curious how it feels, well, pretty damn good. I’m not accustomed to hard work begetting rewards, I had grown up with a empirical truth that hard work correlated to nothing more than hard times — thus, you best enjoy the journey — and so far I did. People often ask me a few questions:

Q: did you party like a rock star after getting into medical school?

I wasn’t showered in confetti, I didn’t go streaking down the street (I sort of imagined that’s how I’d celebrate, but alas now’s not a good time to pick up a misdemeanor), I didn’t take an extravagant excursions to Borneo, nor did I go spelunking. How do I celebrate? In a small way, for example “Man, maybe I shouldn’t buy this shirt..wait I got into medical school”. Those small rewards for myself are enough, because like many college students, I was trying to rival a monk on making due without for years — so, now I’m easy to please. Though, I’m amendable to my readers celebrating vicariously for me.

Q: given the smashing debt, why go into medicine at all?

It’s no secret that medical education is expensive in the US. The average medical student walks out about 180K in debt (not counting their previous debt from getting into medical school in the first place). I really had to ask myself this question, because well I turned down a full tuition scholarship to one medical school, and almost 100K from another. Now, I’m left waiting for my financial aid to be process at BU, and I’m not sure if I’ll be paying the bill by myself or with scholarships. I’ll let you all know soon how that worked out financially. Now, this may seem counter intuitive, especially considering how much I spent on applying. But, I think if anyone is going to use that annoying YOLO, it should be a medical student. You see, I grew up thinking I’d never do much for myself, in fact I thought as a child I’d be a trash man like my mom’s boyfriend — I even considered the utility of going to college, being the first to go. So, now that I’m going, I decided to just go for it. The person who inspired me to take that chance was my research mentor, and pseudo older brother.

Now feelings aside it’s an investment, because even if I spent 180K on lottery tickets tomorrow, I’m still statistically very unlikely to receive a return that makes the investment worthwhile. I believe that a good ratio of your pay to investment of education is your expected salary versus the investment, obviously you’d like to make more than you spent. So, for example, if you paid 60K for a masters I’d think you’d like to make around that amount annually to stay financially solvent (because I am expected to pay this money back). With that example, you may pay for 60K masters and make 20K for 10 years, this would be a great intellectual and personal investment but perhaps not a financial one. On the other hand, if you paid 150K for a BA in Underwater Basket Weaving, then you may be in for a rough ride if you don’t have a follow up plan. I don’t expect to buy a island in the Caribbean, put showgirls through college, or play golf with the mayor. Heck, I grew up with one solid dream, that is make enough so I have: running water, power, and have a home (because at some point in my life I’ve not had one or more of those). Besides, how many people actually get paid to do what they want to do? So I feel pretty lucky.

I’ll keep you updated about my financial aid package (or lack thereof) in the coming weeks, should be coming soon. Be ready for the possible massive face palm, or the lackluster celebration on my part. On the side note, I think there’s something almost liberating about owing a 1/5 of a million dollars — it really puts every day expenses into perspective, and I find myself rewarding myself a little more than I used to.

#doctorbust find me on twitter @doctorORbust

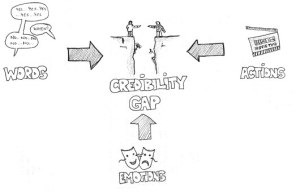

Framing Your Narrative

We live in the age of propaganda. Oh, few words have had their image tarnished like the word propaganda. In the 19th century, propaganda became affiliated misinformation, even to the extent of libel and slander, often to influence others into nefarious activities they wouldn’t of engaged in otherwise if the “whole truth” was known to them. However, the word actually stems from Latin, and it neutrally means “to spread“. We probably would recognize the word better as “to propagate” (e.g. the action potential propagates via..). It suddenly takes on a hint of positivism, well, all depending on what you’re propagating. And, premeds are charged with writing one of the best propaganda campaigns in their career, their personal statement. I assume, that you are possibly like me, okay with science but a little on the weak side when it comes to the touchy-feely part of life. The AMCAS requires these icky things called “feelings”. There was probably never a time in a premed’s career (except breadth courses perhaps) that how they felt, or expressing how they felt, ever mattered or was considered a valid answer. In fact, we are taught to be objective in our manner, steadfast in seeking absolutes, while discarding the subjective as meaningless — after all, if something is a different color just depending on the angle viewed, what’s the point of arguing about what color that object is? It’s all relative. Though, a qualification of my whole argument there is you’re just as inept as I am at expressing myself. But, sharing my thought process and I strung my personal statement (narrative) together, maybe this post will help you.

As you may already know, I sometimes offer to read applicants personal statements and make critiques. Most personal statements have great content, or have the potential to be great. Some are written better than others, as it’s reasonable to expect. So, when I read premed’s personal statements, their “argument” for being accepted into medical school, the personal statement, often usually a series of stacked explicit cliche premises: compassion, passion, lifelong learning, diligence. A superposition of valid premises neither the less — though, it often comes off as a check-list of accomplishments. Often I feel, the problem is not that they don’t have a good story, it’s rather that they haven’t considered their narrative. A lot of applicants have exceptional stories, but poor narratives.

Framing the story with the Narrative – Being a Puppet Master

One thing all premeds need to realize is that, on paper all applicants are pretty have identical premises for admission: good scores, medical & non-medical volunteering, interested in helping people, appreciate the ability to learn, and possibly have conducted research and/or various types of leadership positions. Therefore, simply rehashing your statistics and achievements isn’t really a maximal use of the personal statement in my opinion. Now, don’t let me mislead you — there is an importance in using the typical premises albeit in a nuanced manner. The only problem arises when applicants think retelling their story for the personal statement constitutes a “personal” statement. Instead, applicants would do better to structure a narrative, and string together their story to support “their narrative”. There is a time and a place to leave things up to interpretation, a story’s significance is often left to interpretation, whereas the narrative is typically more concrete. Now, if the reader agrees with the narrative or not is another issue, this will depend on if the story (anecdotes) presented cogent arguments to sway the reader in favor of the author’s position. Of course, you could decide to get artsy and leave the narrative ambiguous, also known in theater/screenplay circles as the Rashomon Effect, but in this type of writing I’d advise against it. A good narrative doesn’t strong-arm, nor coerce the reader into conformity; instead, a good narrative will help to orientate the reader around the premises. And with any luck, the reader and the author end up with the same conclusion.

Building the Bridge from Dreams and Goals — Let’s start with how it ends.

What exactly is your goal — is it just to get into medical school? It may seem like a rhetorical question, I mean, why would you apply if you didn’t want to get in? But, consider it for a second. On your goals, do the curtains drop once you’ve posed selfies on white coat day? Not very likely. You probably want to do well in medical school, clerkship, residency, into attending. Yes, let’s just assume you’re 10-15 years in the future, and practicing medicine and helping new residents. Now, look at your personal statement, and ask yourself do your premises for your acceptance congruent with your picturesque ending? If you think about it, this is likely how far medical schools are also projecting into the future, as they not only care about you getting in, they also want you to be a stellar doctor to represent their program after graduation. I found, this retrograde synthesize method of writing to really help whenever I’m in a writing rut. So, instead of just rehashing your anecdotes, work on your narrative as well.

Each paragraph gives you the right to compose the following paragraph – transitions should be logical to frame the narrative, you’re not trying to make a Memento type personal statement. If your personal statement doesn’t make transitions well, then it’ll appear that there are logical leaps between premises. Transitions don’t have to hammer the reader on the head, but it should allow a ready to easily conclude why each paragraph or sentence supports the rest of the composition.

If you haven’t developed a narrative, try this: take your rough ideas, outline etc, to see if your narrative fits that. Try different narratives, people love narratives. If you’re not sure if your personal statement captures your narrative, have a few friends read over your personal statement and ask them to write a 140 character, a succinct (tweet) summary about what they think your narrative is. The key is to keep their translations short and sweet, if they have to fumble for paragraphs to define your narrative then you’re probably missing something.

Remember, if you don’t chose your narrative your reader will.

Examples: Reefer Madness – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reefer_Madness

Narrative: marijuana use in all forms is destructive to society

Story (anecdotes) premise 1: innocent youth gets entangled with under world due to marijuana cigarettes(aka reefer, Mary Jane, whacky-tobacky, the Devil’s Lettuce).

Story premise 2: usage of marijuana causes: increased sexual activity, suicidal thoughts, and possibly psychotic murderous episodes.

Story premise 3: if only Johnny didn’t use drugs, he’d not be going to jail, and several people would still be alive.

Validating the narrative is simply a matter of validating the story’s premises, or anecdotes. If anything, we should learn that a composition will back fire, if the premises/story and the narrative are not well aligned. This is evident by how ineffective this propaganda movie was towards curbing marijuana use in the United States.

So, again, if you don’t make your narrative others will make it for you. On the other hand, if you make a narrative and the premises aren’t supported, then that’s possibly worse. And, as you should learn on the MCAT, you don’t have to agree with the premises in order to validate the premises. You can totally disagree with the philosophy of the writer, but if their conclusions are valid they are valid. Though, valid priori don’t always mean that the conclusion is supported. Write with the conclusion always in mind, and stack your priori in a logical way to argue why you should be accepted. Use the same (or better) critical thinking tools you used to break down the support and structure of the MCAT verbal passages on your personal statement–at least you can feel better about not wasting your time on that section.

Find me on twitter @doctorORbust

Personal Statement Part 2

https://twitter.com/masterofsleep

Welcome to Part 2 of the Personal Statement (PS) write up. This entry will focus on grammar and style.

- Forming the editing committee

- Rough draft stage I (content focused draft > grammar)

- Rough draft stage II (grammar & style)

- Rough draft stage III (re-center focus on content and flow)

- Finalizing draft stage IV (show mentor PS & get feed back)

- Finalizing draft V (style & flow & cutting back)

- Final Draft VI (send out final draft to all editors)

*Steps 4-7 are straight-forward and will not be discussed further in detail

At this phase of the game you should of found your Personal Statement editing and review committee discussed in part I, or at least found a few reviewers to edit and give feedback on content early on. Don’t worry about the number for now, you can always add (or remove) members later if need be, just get it started. However, in order to use your team to its best ability you’ll have to first deliver to them a good draft for them to work on. Therefore, you shouldn’t give your reviewers piecemeal excerpts or lily-liveried attempts, it’ll just frustrate your reviewers and you. Now, before you write your draft for your Personal Statement make sure you have the right tools: resume, curriculum vitae, possible publications etc. If you’re not familiar with the term curriculum vitae then imagine it as your “scholarly resume”. Resist the urge to drone on all every detail of your life, you’re probably interesting, but you’re probably a lot more compelling in person. And, the point of the Personal Statement is to get an interview, that’s it. Accordingly, the interview will be sent to you because they wanted to meet you from a combination of your application and Personal Statement. And they wanted to meet you because you were qualified like everyone else and something special about you, this should be captured in the Personal Statement. You’ll have lots of moments to expand upon your qualifications, to a point where you’ll feel nausea after spending so much time talking about yourself – remember, after the Personal Statement there’s plenty left of opportunities to clarify your qualifications on the primary application and secondary’s (oh the secondary horror). General things to write about on your personal statement:

- Introduce who you are, and why/how your individuality will make you a positive impact on the medical school if accepted. Don’t exaggerate.

- Be congruent on how your inclusion in the medical field, specifically as a physician, will have an impact on the community you will serve.

- Identify when and why your interest in medicine came about. Be sure to differentiate why a physician as a career and why not any other equitable ways to deliver positive health care outcomes.

- Project your career as a professional and physician into the future where you serve the public (e.g. 10 years after starting medical school).

There’s some Heisenberg Uncertainty when you try to write and edit simultaneously.

So, let’s begin with the writing portion, and then we’ll get into the joys of wearing your editor’s hat. We won’t go down a philosophical debate about it, let’s just agree on this for now. College got us into a bad habit of producing papers like they’re hotcakes; any decent premed could pull out an A- paper about the ethics of wombat plastic surgery last minute. I won’t lower you down to my level of bad habits while in college, but I will say I was a successful rough draft warrior. It wasn’t actually until I graduated college and was paid to write that I sat down and took the task seriously, after all I needed to save up for medical school applications and pay bills. My tip for you is to have a “writers” mindset and an “editors” mind-set; the two processes are copacetic but disparate beasts. Sit down and write down your first rough draft as a passionate writer, while keeping the general points to address I listed above, again emphasis on ‘rough’, let the writing flow:

- Leave the thesaurus at out of the picture unless the word you’re trying to imagine is on the tip of your tongue. Keep your language simple and loose, in fact I would encourage you to tone down superfluous language when it renders the clause less intelligible than simpler alternatives (see what I did there?). Words are meant to communicate an idea in the best way possible, not to project intelligence, use substantive examples instead if you want to project your intelligence. In other words don’t use expensive words for a bargain bin idea. If you’re naturally a word-smith, or want to use that GRE word-list you resentfully studied, go ahead and do what works for you but tread lightly. It’s analogous to cursing or using all caps to show people online you’re angry.

- Don’t worry about the character limit of the Personal Statement; feel free to go well beyond it on your first draft. It’s very likely you’ll toss out a lot of what you’ll write anyways in favor for more efficient and elegant versions. So, the priority here is to get the ideas on paper so you can whip it into shape later.

- Grammars edits will have more substance if you wait until the end instead of editing on the fly. Grammar is important, but it interrupt your ideas, don’t waste your time wearing your editor’s hat now, you’ll tackle that later. Sure, catch obvious stuff and fix it as you feel comfortable, but don’t get bogged down.

Editor Time – Last Grammar – Style Tips When I’m done writing my first rough draft I take the horrendous product and shove it into my grammar machine. I go point by point, assuring that I tackle all of the same issues at once, this reduces my writing time tremendously:

1. Use active whenever possible instead of passive. When I edit people’s PS I notice they often will (perhaps unconsciously) switch to passive voice for unfavorable situations: Passive voice:

“I had the misfortune of receiving a B- in Genetics.”

Active voice: “I learned what it meant to struggle despite trying my after earning a B- in Genetics.”

But, the down side of doing writing passively is — besides making an awkward sentence — the grammar would imply that the writer isn’t taking ownership of their academic black-eye.

2. Ever wonder how to use those fancy dashes but never knew when? Use it as a sudden interruption to summarize a thought or to fly in opposition of the clause before the dash. Try not to misuse or overuse the dash, but it sure does make for a sleek sentence if used but once per essay. “You’ve probably always wondered how to use the dash — if you had cared about fancy punctuation at all — and assumed it was difficult to use.”

3. Replace vague language with concrete language whenever possible. Vague: “An unfavorable air of fear filled the trauma room all day after her death.

Concrete: “After she died the room the trauma room stunk of fear.” I wouldn’t see either sentence is great, but the second one isn’t vague and it carries more weight.

4. Chop out extra words, there will be a lot of them. Typically this entails getting rid of the excess “of”, “have”, “pretty”, “very”, and the sort within your personal statement. I find it more efficient to do this all at once. For example, I sit down with a goal of reducing the amount of “of” usage. If you’re used to using Twitter this should come natural to you. This is functionally easy to do, just use your search function to go on a search and destroy machine on wasted words.

5. Avoid a common problem, never use a fancy word if you’re not sure how to use it. While you’re at it, be sure to avoid using words that don’t exist for example “irregardless” is not a word. Check out Wikipedia for an entry on common misused words: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:List_of_commonly_misused_English_words

6. Avoid vague and overused words like “interesting”, “passionate”. Instead, demonstrate it. Instead of saying:

Snore festival: “I am very interested in medicine because I’ve always had a passion to help people.”

Exemplify your “passion” with an anecdote from your CV/resume material instead of relying on cliche words. Another good word to avoid is “surprisingly”, or “literally“, I could literally go on forever. If you’re curious about what other words are destroying your personal statement Let’s face it, few things are really that surprising, so if the word is used the result better be nothing short of astonishing. While we’re making lists also try to avoid using: dynamic, intense, team player, people person, dedicated. Remember, show, don’t tell.

7. Avoid overusing using “-ly” whenver possible: amazingly, perceptively , stunningly It’s okay to have a few “-ly’s” every now and then, but I’ve been told it’s analogous to putting a top hat on poop. It’s still poop.

8. Make sure you didn’t comma splice, use semicolons when appropriate. Conversely, people tend to gain a fear of comma splicing during college, so they instead break a good “one” sentence into “two” — avoid this. If this makes no sense to you, assure your grammar editor is comfortable with it.

9. If the sentence makes just as much sense without a “word” that word probably isn’t necessary, consider getting rid of it. The same goes for any sentence when compared to a paragraph, a paragraph when compared to the PS.

10. Avoid exaggerations on your achievements or insights. It will make your reader think you’re a tool: “When I shadowed Dr AnPanMan I felt so invigorated by the spirit of medicine that I knew there was no other path but medicine for me.”

Added 1/17/14

11. Devote a set time to editing, and be deliberate about what you’re trying to correct. However, don’t try to finish your editing all in one session, it’s too laborious and you’ll make mistakes. Instead, after you have your draft finished work on corrections every day for 20-30 minutes (or every other day if you feel stressed out). Sometimes the best thing you can do to improve a piece of writing is to walk away from it, and then approach it again from a different perspective.

12. I’m not sure if the editing ever stops, but at some point you have to be satisfied (in case your curious this entry has been revised about 25 times, including this one). In fact, about 3-seconds after I submitted my AMCAS application I thought of one more edit I could do on my PS. Arguably some of your best ideas will come after your submit your application and it can’t be returned to you.

Well, that’s all I have for style for now. If you’re a foreign reader and would like to hear more about grammar or style I wouldn’t be your expert, but I can refer you to some great free online material.

Well, that’s enough reading about the PS, get cracking!

About my writing background:

Besides writing my own Personal Statement (PS) I help my Twitter family with theirs when possible. I learned how to write more systematically when I was charged with writing five health and fitness articles per week, the threat of getting fired helps motivate you. Currently, I sit on an Institutional Review Board and Animal Care and Use Committee where I review research protocols to ensure they meet local and federal regulations about protections of research subjects — another writing heavy job. My other gig I currently pull off is an interim position where I review applications from research scholars, help organize conferences, and distribute stipends. You’ll never escape having to write. If you personally want to write better, or are foreign born and want to surpass your native buddies I’d suggest picking up a rather old book called Elements of Style on Amazon (or free at http://www.gutenburg.org; you can hug me later).

Best,

Accrued Medical School Costs: With Fancy Numbers

twitter: https://twitter.com/masterofsleep

This post will be devoted to discussing how much I’ve spent so far on applying to medical school. Applying to medical school is pretty pricey as you probably already know, I knew this going into it. I tried to adjust accordingly, paring costs when possible. I’ll be the first to admit that I didn’t really want to sit down and calculate my costs, it’s sort of depressing to see the final number because I’m currently pretty poor and my car isn’t even running. Good times, but hey, I’m going to be a doctor!

People have asked how much have I paid in total, it’s a hard question to answer because the process of applying to medical school can extend into April, and it has multiple phases. Although, the secondary application period is closing soon, so schools will no longer accept secondaries and will only be issuing applicants a series of responses: interview invites, and acceptances, wait-list, and rejections. I can only gain an acceptance after interviewing, but I can be rejected at any point of the AMCAS application process. As for me, like many others, I am in the interviewing stage of the process, and there’s a relative calm so I have time to reflect and lament on my lightened wallet.

Save yourself the headache and sacrifice a goat to receive FAP, I didn’t get it but go for it, a lot of people do receive it!

So you can better compare your costs with mine I’ll layout my own experience. I didn’t qualify for FAP, if you did then your costs won’t be as high as mine, so don’t be discouraged there’s hope! Myself, it was a Catch-22, the FAP uses your parents tax returns regardless of your independence status and age. A similar situation happened to me when I was young and applying for FAFSA (FAFSA will finally separate your parents W-2’s when you hit 25), not a great system for those who fall through the cracks.

For the primaries I applied to twenty schools, then from those twenty I completed twelve secondaries. From those twelve secondaries I have received eight interview invitations and one rejection, I’m convinced the other four schools set my application on fire. I was offered four acceptances, I took three and turned down one school. It’s best to withdraw acceptances if you’re truly not interested in attending to make space for others who might be wait-listed. I am awaiting to hear back from one more school this week, if I got in it would mean a lot to me. I also have one more out of state interview lined up that I’ll probably cancel later this week or the next — especially now that I’ve calculated the cost so far.

You might of wondered what happened to the other eight or so. One school I withdrew my primary because I changed my mind about their program. I received two rejections: school 3 primary alone, school 4 after completing their secondary. It didn’t sting that bad because I was already accepted into one program by the time I received my first rejection — I applied very early and interviewed on the first date available. School 5-8 I didn’t complete their secondaries because by that time I had two interviews (including my top choice) completed, several lines up, and I had received two acceptances by that time.

Primaries alone:

I applied to 20 schools during primaries, the first school was $160 and $35 thereafter, so my primaries cost: $860

Secondaries alone:

I completed 12 secondaries (*update 13 II), the prices ranged from a ‘low’ $85 to $150, I’ll go with the low end of $110 per secondary as an average so that makes the secondaries: $1,320

Primary + Secondary: $2,145

Interviews (flights, room & board, transportation):

I have attended 5 interviews so far, all of them a few time zones away. I couldn’t group two of my interviews together, but I was able to group the other three together. Grouping them together is pretty stressful logistically, mentally, and physically, but it’s a lot cheaper to buy a multi-stop ticket than not. To shave costs on room and board I stayed with hosts whenever possible, in one state a friend on twitter housed me (go technology). In case your curious I booked everything on Priceline, and I downloaded an application on my phone to make finding rental cars easier and find coupons.

Plane tickets – $1,800

Hotel – $1,000, I slept in O’Hare Airport on one night *not fun*

Food – $300

Car Rentals – $400

Suit (tailoring for charcoal assemble – $200

Interview total cost — $3,700

If you can be competitive within your state you can skip a large chunk of these costs. If you are from California sign up for frequent flyer miles now.

Time off work: another $1,000

Deposits for acceptances: although I was offered four acceptances, I turned down one, and took three acceptances (two didn’t require deposits, and one didn’t). So it cost me ‘mere’ $100. If I get accepted into the program I’m waiting for next month then I’ll have to plop down a cool $500.

Well, that brings our grand total thus far to $6,980 or $7,480 if I was accepted into my top pick — fortunately, I do get the deposits back in a few months.

Estimating your costs:

So, here are some projections if you apply to medical school the primary applications will cost you in dollars: f(x) = 160+35x (x is #schools for primaries ). However, the cost of the first application may change over time, so let’s assign this a constant, so the first application is $160 + f (x). The secondary applications, g (x),will run you anywhere from 85y and 150y, but really probably somewhere around 110y (where y is the number of secondaries you complete). It’s possible and very likely you won’t complete as many secondaries as you did primaries, that is why I made x and y separate independent variable. However, it is obvious that y is dependent on x, that is the number of schools you get to apply to for secondaries is related to your primaries. So, all that’s left is to make a representation for the cost of interviews, this will vary from none, to a deluge. I can’t predict if you’ll apply in state only etc., so let’s just agree to call all interview costs C. So, the fruit of this dry paragraph is the following equation for you to use to estimate your AMCAS cost (not including the MCAT and possible deposits, variation in application strategies etc.):

cost = A+35x+110y+C , where A = 160, and C varies by person. So cost = A + f (x) +g (x) + C

- A = $160, cost of first application. Cost my change over time.

- x = number of schools you apply to during your primaries. A lot of people apply to around 15-20 schools.

- y = number of schools you put a secondary through, it will be equal or less than x. I went with a conservative $110, you can try anything from $85-150 if you want a range from super cheap to top dollar.

- C = estimation of room & board costs, misc costs.

The largest part of applying to medical school is commitment, I like to consider this sacrifice of my blood to be some type of rite of passage. A symbolic token to say that I’m serious about medicine, at least that’s what I tell myself when I empty my coffers.

Here’s a table of the expenses you should expect at the minimum assuming the fees I stated before:

|

#Schools Applied |

Cost of 1st |

Cost of 2nd |

Cost of 1st + 2nd |

|

1 |

195 |

110 |

305 |

|

2 |

230 |

220 |

450 |

|

3 |

265 |

330 |

595 |

|

4 |

300 |

440 |

740 |

|

5 |

335 |

550 |

885 |

|

6 |

370 |

660 |

1030 |

|

7 |

405 |

770 |

1175 |

|

8 |

440 |

880 |

1320 |

|

9 |

475 |

990 |

1465 |

|

10 |

510 |

1100 |

1610 |

|

12 |

580 |

1210 |

1790 |

|

13 |

615 |

1430 |

2045 |

|

14 |

650 |

1540 |

2190 |

|

15 |

685 |

1650 |

2335 |

|

16 |

720 |

1760 |

2480 |

|

17 |

755 |

1870 |

2625 |

|

18 |

790 |

1980 |

2770 |

|

19 |

825 |

2090 |

2915 |

|

20 |

860 |

2200 |

3060 |

Thank GSM for the 99 cent store.

Letters of Recommendation: How Do I Get Em’

Contact me on twitter: https://twitter.com/masterofsleep

Welcome back,

Applying for medical school is an odd process, especially if you’re a nontraditional applicant. For myself, I rushed to complete the premed requirements and my major/minor/undergrad research. After being molested by academia, you’re thrown into the hardest entrance exam in on the planet (no hyperbole) for 5-6 hours. Then you are asked to complete several other Herculean feats to complete your medical school application, abbreviated as the AMCAS:

- Primary Application

- Scores: MCAT, and GPAs (two separate undergraduate GPAs will be calculated by AMCAS), a masters degree will not shroud undergraduate GPAs, it will however show improvement.

- Personal statement: bust out your feather quill to write the best personal statement you’ve ever written — no, the one you wrote before won’t do either.

- Work Activity Section: I’ve already covered this in another article.

- Letters of Recommendation: this article will focus on obtaining a letter.

So, I’m often asked about the subject of “Letters of Recommendation” (LOR, or LORs when plural), I’ll tell you how I handled them in this article and attempt to answer the following three FAQs:

- From who do I get them from, and how important are LORs?

- How do you I ask letters for a recommendation?

- When do you need to start thinking about letters of recommendation and what is the timeline?

- From who do I get them from, and how important are LORs?

Most medical schools accept two types of letters individual letters and/or committee letters. If you are traditional premed then go with whatever your premed adviser suggests as the standard protocol for other premeds from your university who have been accepted. From what people tell me, that usually entails obtaining a committee letter if you’re a traditional premed. However, as a nontraditional I had no idea if my university actually has a premed committee, nor did I care to receive premed advising as a late entry nontraditional. Thus I obtained individual letters from various professors — so this article will focus primarily on individual letters. In my own case, having individual letters seemed to work out because I was offered four acceptances by mid winter. There are probably pros and cons to either form, for example committee letters are probably logistically a lot easier to obtain and they probably know what to write to make you look like a good applicant. The downside (just to play devil’s advocate) is that you’re really hedging all of your bets on the committee who probably don’t know you very well personally besides the occasional meeting. The upside of the individual letters is that if you chose you writer wisely you’ll end up with a very exceptional personalized letter. But you could also chose the worst person to write a letter for you, and on top of that you’d have to handle all the logistics of making sure your letters go to AMCAS on time on a case per case basis. Before committing to schools be sure to check with each school’s policy because sometimes they do have very specific requirements.

In my case, my individual letters were:

- Human Physiology Professor and my research principal investigator

- Chemical Engineering Professor and the chair of my research scholars program

- Chemistry Professor and research adviser for research scholars program

- Political Science Professor who I volunteered with for prison education programs

- The dean of my major

I chose writers who could vouch for what I felt were my strengths like work ethic and science background (letters 1, 2,3,4), my commitment at bettering my community (letter 4), and someone who could vouch for my patient experience (letter 5). If you have individual letters coming in, use them to compliment your AMCAS. My principal investigator worked together quite intimately, so they also had no problem ameliorating my perceived shortcomings for the admissions committee. I had all but one of them upload the letter electronically after I gave them a written tutorial about how to upload it to be sure it arrived on time.

Either way you choose, individual or committee letter(s), there’s no way you can guarantee the admissions committee will see the writer’s arguments for your admission as satisfying or cogent. It’s hard to quantify how important LORs are, because we have to consider a lot of variables such as the rest of your application and letter quality, but I’ll just say in my case my letters came up favorably during all of during my interviews (unless they were not given access to the LOR prior to the interview). So, I think it’s probably safe to assume they’re important and shouldn’t be thrown together haphazardly, the quality and amount of effort you put into obtaining good LORs will correlate to better LORs.

- How do you I ask letters for a recommendation?

You may be in school or out of school, either way the strategy isn’t that different. Now, I work with professors everyday for work, and I see how busy they are and how to get through to them. Check online, go to their office hours. Bring transcripts with overall GPA, classes you want them to see highlighted, plus any other recent accolades. Tell them why you want a letter from them specifically, when you intend to apply, and when you’ll need the letter by. If they agree give them at least 6 weeks (make the window too short and they’ll refuse, too long and you’ll never get a letter finished). Even if you obtain a verbal confirmation that they’ll write you a letter, be sure to follow up with a formal request for both your records by email, it’ll help keep the record straight for both of you. Remember, your letter writer probably doesn’t have time to write you letter, but they’ve kindly agreed to postpone their other responsibilities for you.[[ (quick reference): [insert Corran letter] I asked for all of my letters in person.]]

If possible make in person verbal requests, bring nothing with you but a succinct explanation of why you want a letter from them, and verbally confirm they can write you a “strong” letter of recommendation. If they agree to write you a strong letter then tell them you’ll follow up with a written email with your transcripts/stats, and means by which they can submit the letter. Some professors will tell you directly, “I don’t think I can write you a strong letter”. It doesn’t necessarily mean they curse your existence, they’re probably being honest because it translates to “I don’t know you enough to write you a strong letter”. On the other hand, in the unlikely event that they actually despise the day you were born and have a picture of you on their dart board, you wouldn’t want one from them anyways right? Don’t take it personally if they refuse, they’re likely doing you a favor by saying “no” either way. If they say they can not write you a strong letter of recommendation thank them and move on.

Follow up with a very easy to read email. Now, I assume your writer will be an excellent reader, but they don’t have time to read through a gregarious lengthy email. Furthermore, they’re putting their “street cred” at risk as a professional by attaching their name to yours, so it’s quite an honor to receive a strong letter of recommendation, make sure you’re doing your part to make it easier on your letter writer. So keep it short and sweet and unambiguous, so be sure to include in the formal written request:

- Let them know the exact name you used to registered for AMCAS as well as your AAMC ID#. Remind them the letter requires an official letterhead.

- First and foremost, thank them for agreeing to write you a strong letter by a specified date — letters will likely roll in late if you rush the writer without prepping them properly or allow the responsibility to fall onto them to ensure timely completion.

- Give a very brief narrative about you and your intentions (a short paragraph).

- Stats: give them a summary of your GPA/CV, favorable or not. For their peace of mind include a PDF attachment of your transcripts/CV, let them know it’s attached and the correct title if you have multiple attachments. Highlight the pros of your stats, offer to talk more in depth in person about personal circumstances that may of left bruises on your transcripts.

- Concretely tell your writer what types of things you’d like them to address.*

- Give them a concrete way to submit the application. This will mean giving them the physical address of the AMCAS letters service if they want to go snail-mail, or providing them the links and steps to upload your letters online. If your letter writer finishes the letter and can not send it because of poor instructions it’s not the fault of the writer.

Don’t be surprised or insulted if the professor who agrees to write you a strong letter first requests for you to draft a letter of recommendation for yourself then submit it to them to modify as template (it’s very common in the research world). Above all else you should always know your strengths and weaknesses of your application. Use this knowledge form a draft that shows your good points and rationalizes the humps on your application without making excuses. There’s a good chance that the LOR they actually send will appear nothing like your draft, but the highlights you wanted will likely still be captured.

- When do you need to start thinking about letters of recommendation and what is the timeline?

You should start thinking about who would make a good candidate for strong letters as soon as possible. The sooner you understand the strengths and weaknesses of your application the sooner you can start pulling together your writers. If you’re afraid of writers forgetting about you later, let them know about how you’d like a letter later, and send them an email as a record to confirm the confirmation. When it comes time to ask them later, you could pull that record up to help refresh their memory.

Give your writers ample time to compose a good letter for you, if you try to drop a bombshell on them at the last second don’t be surprised if you get a mediocre letter or if they outright refuse out of principle alone. You can turn in your primary AMCAS application prior to receiving any letters, however schools will not invite you post secondary application unless you’ve submitted your LORs they request for their program. So, it’s important to consider the timeline when you’re requested strong LORs. I approached my writers formally in April (primary applications open in June) and I gave them a deadline of the 3rd week of May. This gave my writers enough time to compose the letters, and enough time for me to discretely nudge my writers when they were falling behind.

In closing…

The amount of preparation and methodology you chose to use to obtain your LORs will have a correlation to the LOR quality submitted. If you put in the minimal amount of effort then expect a minimal LOR. Also remember, your writer (especially professors) are putting their reputation on the line, so be courteous and respectful. Be sure to thank your writers after the process, and keep them up to date on your progress or lack-thereof (as a tutor I really loved when students got back to me about grades or when I wrote a rare LOR for them). Be honest, respectful and appreciative while constructing your professional network with your writers.

Have something to add about your experience with committee letters or individual? If so, feel free to share.

Thanks for reading, and feel free to contact me anytime https://twitter.com/masterofsleep

*updated on 12/18/13 Added something about the letterhead. Thanks SDN user.