AMCAS

Interview with Incoming Stanford M1 Accepted

Hello Everyone!

As promised, here’s the confidential(identity) interview from the accepted Stanford student. They’ll be starting this year as a M1. As a nontraditional premed, switching majors several times before finally deciding to apply to medical school.

It’s interesting to note we both applied to Boston University and Stanford, however we both never received interview invitations from each other’s respective current medical school — it really goes to show there’s interpretation about what constitutes a good fit for their institution, and we found our own fit. For myself another interesting point of this person is that, like me, it took them many years to finish their college career — we both took multiple breaks for work and switched majors innumerable times before deciding on applying to medical school.

Anyways, I had to distill a nearly two hour conversation where we easily went into tangents (mostly entirely my fault). After laughing and removing the tangents, here is the more educational and likely useful results:

Q. 1. When did you decide that medicine was for you, and why?

Basically, I realized medicine could be a career for me because of the position it occupies in relation to other fields. As a community college student, I had the opportunity to take a wide variety of classes in different fields, without needing to prematurely declare a major. I had always been interested in fields where I thought I could make a difference, I dipped my toes in psychology, sociology, political science, “hard” sciences (thought about a PhD), public health, and even art (documentary photography). For me, medicine fits snugly between public health and the hard sciences, and gives me the best of both worlds (well, what I feel is the best of both worlds). Public health was hard for me because it was a bit far removed from the individual level, obviously since it’s more focused on populations. This is great of course! But that was hard for me to work with, because actually seeing change takes a LONG time, if you see it at all. Bench research is cool too, I still love it, but couldn’t see myself devoting my life to it because it was easy to get caught up in the little things, without the human perspective, and I felt a little lost there, honestly. Medicine allows me to inform both fields with a clinical perspective, work with both fields as part of the health team, and still enjoy what I do

Q. So, do you think being a nontraditional gave you a different point of view? For example while studying.

I think so. I can’t say that more traditional premeds didn’t learn the same things I did, but I can say that I wouldn’t have the perspective I do without doing it my way. Having studied a variety of topics, I kind of felt that medicine was just one career path that could be taken. It fits a small niche in between all the other things people can do with their lives, or to help others. Plus, being nontraditional, working through school, all of that…I had to learn to prioritize and really figure out WHY I needed to do some of these things. I think premeds often get caught up in “the list”, the list of shit we’re supposed to do to be competitive. And a lot of us end up with huge resumes of shit we did that had no impact on us or our communities

The end goal is to be a great doctor…so these experiences should be towards that goal. Activities aren’t just there for filler. Med schools look for these activities because they think we have something to learn from them. And as a nontraditional student, I think I may have had an easier time figuring that out

Q. Lately, schools have really been pushing for diversity, how do/will you bring diversity to your program?

As for the diversity question…I STILL have trouble answering it. I think it’s because there’s no single factor that stands out as HI THERE DIVERSITY. I’ve mentioned before that I am certain that all of us are really diverse. We have our collections of scores and activities on the applications that look the same in bullet-point form, but different students get into different schools. In any case, I think being a nontraditional premed has given me some interesting opportunities. I took extra time in school; it took me eight years to finish up my degree, so I was able to explore a number of different areas of study and work part-time throughout undergrad. After all of that…I can’t help but see medicine as integrated with every other field, and my approach to healthcare in general requires that we don’t separate “health” from the rest of our patient’s lives. I also had time to make big commitments to projects that I cared about, and learned more than I could have imagined. I helped get a nonprofit global health organization started, which taught me as much about public health as it did about team work, leadership, and resource management. I worked in a research lab for a few years doing more engineering-based health projects, and was inspired by the potential future of stem-cell based diagnostic devices and therapies. I think the biggest opportunity I had while being nontrad, and perhaps bringing some diversity to the mix is my restaurant work history. I got my first job at 16 working in a cafe and bakery, and from there moved on to other cafes and finally ended up serving and bar-tending at a restaurant as I got older. It seems like working during undergrad isn’t typical for a lot of premeds, so I’m so glad I had a chance to do it. Of course, I hated it at the time and it was stressful, but being forced to talk to strangers day in and day out will probably help my bedside manner more than any amount of shadowing doctors could do. I learned a lot about making people feel comfortable and responding appropriately to misplaced anger by waiting tables. Although it isn’t directly related to medicine, waiting tables taught me a lot about professional communication in strained situations. People can get really upset about their food, it seems! Or parking, or having to wait for a table…about a lot of things outside my control. And I feel that happens in everyday medical practice often, so having a little bit of experience managing those situations will likely help me in the future. Waiting tables was also a great teamwork exercise; you really can’t survive the floor without working together, even if you don’t always get along with your coworkers. Maybe that gives me some of that coveted diversity? Who knows, I think it’s the summation of our experiences that gives all of us a unique perspective.

Q. So, as a nontraditional or traditional premeds was there anyone who mentored you? Also, applying to medschool is pretty nebulous; have any guidance or tips along the way?

I’m lucky to have had a great mentor in this whole thing. I think as you’ve pointed out a few times, there are a lot of people who are just waiting for us to fail, to not make it. So, I had my mom, who is a doctor and a teacher. When I have questions about how to be a great doctor, I always turn to her. For the premed-y things though, I kind of just went with it. Internet-searching. Berkeley doesn’t have official premed advisors, so I kind of went at it based on anecdotes from friends and the internet

As for my tips…I think the best ones I have are to do what you love…pick a few key activities that will help define and shape you, and give them your all. Don’t mess around with 100+ random activities that you only contribute 10 hours to.

Also, keep a journal of everything. Not only does it make it so much easier to learn from and reflect on your experiences, but you will thank yourself SO MUCH when applications roll around.

And surround yourself with good people, even if they’re not premed or doing the same things you are. Don’t let negative folks discourage you, don’t take SDN too damn seriously, and don’t put other people down because we never know where they’ve been

Regarding the question of, “For premeds without a committee or reliable advisors do you have any tips?” that’s a hard one. Reliable information is difficult to come by, and you don’t want to get sucked into the anecdotes too much, because they may be wrong! I think some of the books out there are pretty good –the ones written by previous admissions officers. I guess my major tip for anyone is just always frame your activities or potential activities by thinking “How will this make me a better doctor? What am I learning or contributing?” If you can come up with solid answers to that, then it’s a worthwhile activity lol.

And the usual: don’t let your GPA slide, set study schedules to keep it up, check school websites to meet prereqs, and don’t think the MCAT will be a breeze.

Q. I suppose you should probably jot down that answer [from the journal etc.] as well for later during secondary/interviews?

- YES, absolutely. Take notes, always. Makes life so much easier down the line when time is of the essence. I was lucky that I had some notes and journals, but I WISH i had an updated CV.

- Oh…another pro tip. Start saving a lot of money — like yesterday. Charging app fees to your credit card is awful (that was me, it sucked).

Q. As you already know, I don’t report MCAT scores; but, you did very well, do you have any study tips?

Well, since everyone studies a bit differently, it’s kind of a hard thing to say for sure. The one thing that I think will work for everyone is to set a study schedule. Like map out every single day, what you’re going to review, how many problems you’re doing to try, etc. Even map out your break days

- I also tend to think that you shouldn’t review all of one area, then the next. Should probably do one chapter of physics, one chem, one orgo, one bio, then repeat with the next chapters

- Practice problems are golden, obviously. do as many as possible, but I think it’s best if you don’t re-do the same ones. I saved all my AAMC practice exams for the last month

- Flashcards are great for random facts, and can be taken anywhere for quick review (on the bus, between classes, etc)

- Always focus on understanding and connecting concepts, rather than memorizing shit

*Doctoorbust: a caveat, remember pick tips that work for you, ignore any that don’t.

Q. I know you’re tired of hearing this but, any idea what you’re going to specialize in?

Not a clue! I’m trying to go into it with an open mind, simply because I know I haven’t seen even half of what specialties are out there. Even for the ones I have “seen”…it’s difficult to know if my experience in them as a premed was anything like the way they actually are. So, I’m trying to be open.

Plus, it’s hard to know where the field will be in 4-5 years. Things change. The structure of medical practice is undergoing some pretty significant changes, and I’m not really sure where it will all end up.

Q. How do you feel about the coming changes (healthcare)? There’s a lot of anxiety in some groups about it.

I honestly don’t know. I see it as a good thing, a step in the right direction for expanding patient coverage, but I can also understand the concerns from a doctor’s point of view, as far as who is getting reimbursed for what, and additional constraints on their time I think it is easy for us to say, as folks who have yet to enter the medical field for real, that expanding coverage is GREAT and it’s easy and things like that. But I’m not sure we really know what it’s like in the trenches. I’m thinking specifically of primary care, it seems that it’s going downhill fast for those currently in family practice and internal medicine.

For the record, my personal opinion is that expanding coverage equates to awesome. But I don’t think we can neglect the concerns that have been brought to the table by our colleagues, either.

Q. What are some things you wish you did as a premed now that you’re going into medschool?

I wish I had traveled more, and taken more time for non-premed activities. I definitely enjoyed all the work I did in preparation for becoming a doctor, but I let some things slip too

I would just advise people to always make time for hobbies, for themselves. This is because hobbies are every bit as important as engaging in research or volunteering. Being healthy and happy will make you a better doctor, too.

Maintain relationships! Friends, family, don’t let it slide because you’re too busy studying.

Q. Now, you’ve been there and done that. What are some misinformation points you’ve heard about being a premed or applying that you believe to be false, at least from your experience?

The biggest thing I think is that you need a perfect GPA and perfect MCAT score, or that having X hours of these activities are all it takes. Or that it’s guaranteed to get in if you have those things. And you see this everywhere. “My friend has a 4.0 and a 42 MCAT and thousands of hours of volunteering and research and didn’t get in” or the other commonly seen thing “I need a 4.0 and a 42 etc in order to have a shot.”

Yes, you need decent numbers, but that will only get you so far. We have to learn from our experiences in order for them to count. The hours spent doing an activity are usually correlated with learning and reflecting, but the hours themselves don’t mean anything

The other thing about applying that I saw a lot is the obsession with school rank and the numbers. It’s not all a numbers game. Schools have different missions, different focus points that they look for in their applicants

The smart applicant will choose schools that they will fit into, whose goals are in line with the applicant’s, or the applicant feels he/she can contribute to

The process feels like a crapshoot. To some extent, it probably is, but that doesn’t mean that applicants can’t maximize their chances. Obsessing over numbers won’t get you anywhere. and the thing is, just because your experiences don’t fit into one school doesn’t mean they don’t fit somewhere else. For instance, I was rejected outright from BU! But I got in somewhere. And you got into BU! And were rejected from other places we all have different strengths, just have to play to them. it takes some serious self-reflection and honesty on the applicant’s part. Still, no one’s saying it’s not competitive. But…always remember the numbers aren’t everything. My GPA sucked, and I got in somewhere.

–end–

Thanks for reading! I’ll try to keep posting while moving!

AMCAS II Ex. 6 — When Have you Faced Criticism?

Eventually along the way you’ll find a secondary question asking you about how you deal with criticism. It’s an important question for innumerable reasons. The question for this essay is pretty much asking you, “Have you learned how to accept criticism and then do something constructive without having tantrum?” Medical students receive critiques to hone their skills prior to being flung into residency. Once there in their internship, they’ll be a lot more of it, most will be legit some unwarranted. Other physicians may criticize new interns, these new doctors find themselves bombarded by critiques that are no longer didactic exercises, but are now instead life and death lessons. Patients will berate you for being late, how could they know you were doing chest compression upstairs in room 215 for 20-minutes? But, without getting too far ahead of ourselves, let’s just remember that the medical school wants to see how you will handle criticism when they dish it out to you — there is also an undertone of show your maturity here please.

If you’re not used to handling criticism, you should get used to it. I finally learned what criticism meant when I was just accepted as the co-principal investigator for a project. I turned in my research thesis for my senior project to my principal investigator. He gave it back a few weeks later, but for some reason he had changed all of the font to red. I was wrong, he meant the whole thing had to be scrapped. I faced more criticism during lab meetings where we had to present new or class electrophysiology research articles and our interpretation. After some time, you just learn how to take criticism and become better from it. If there’s room to criticize then there’s room for improvement.

During this essay you’ll try to do several things:

1. Show that you know how to take criticism, i.e. you don’t bite off people’s jugulars when they give you an honest critique.

2. Show that you understand that accepting criticism can be a learning experience — this can be true regardless of who’s “right or wrong”.

3. You can show that you have some real world experience, i.e. will the school also need to teach you “life skills” or do you already have some.

Tell us about a time where you’ve received unexpected feedback or critique. And, how did you react to the situation?

As an Institutional Review Board (IRB) [title redacted] my first and foremost goal is to ensure that research projects meet ethical and regulatory standards. However, principal investigators (PI) often have disparate concerns, namely the timely completion of their investigative study. In one particular protocol conducted by a well-established (PI) I found the protocol didn’t meet my interpretation of ethical compliance. In response, I received a deluge of emails noting my incompetence; it became apparent to me that my review didn’t sit well with my (PI) colleague. I’m not infallible, and there’s a lot of “grey areas” in law interpretations, so I launched an investigation into my own decision. I poured through ethical reference texts and case studies to establish an ethical precedent for my decision, after I proved my case I reported my findings to the IRB and PI. After the protocol was modified, the study was approved and I have a good working relationship with that same PI.

The hardest part of this entry was actually writing it in such a way that I could still be professional, and be certain to represent both sides of the argument. Also note that I decided to not defend some of the criticisms against me, and instead accept it and show how I grew from it.

Good luck!

Diversity — Financial Diversity and GPA

In the last article I focused on diversity and applicants’ socioeconomic status (SES) correlation with the MCAT. This time we will discuss SES and the overall GPA. Gleaning information from the last article we’ve already discussed the following:

- The AAMC and the TMDSAS both have found a trend, the higher the students’ family income bracket the higher their mean MCAT score.

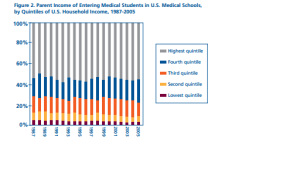

- Just over 75% of the accepted medical students come from families in the upper two quintiles (income brackets).

- Less than 10% of the accepted medical students will come from families in the lower two quintiles (income brackets).

- This trend has been pervasive, but not for the lack trying from the AAMC and medical schools continual attempt at intervention with the introduction of SES consideration & holistic interviews.

-We also most mind the logical caveats in the data:

- Averages don’t equate to a snapshot of any one applicant; SES isn’t fate, either in a positive or negative light.

- Not qualifying for SES status necessarily guarantee both familial support financial and emotionally. I was in this boat, long story short in college I never qualified for SES consideration because of my parents income that I never tapped into. Regardless, I slaved away like everyone else healthy GPA and MCAT score, fund my ability to work for free (volunteering), applications etc.

- We can’t use these numbers to correlate with who works harder, and there will be variations in applicants regardless of SES that would appear within any pool.

This time we will examine the talking point data presented by the AMCAS and TMCAS to examine the following questions:

- Is there any correlation with SES and GPA?

- How is SES related to ethnicity? *We will look at the TMDSAS because of their unambiguous preferences for consideration of SES.

This time we’ll focus on the Texas equivalent of the AAMC, the TDMSAS applicant joint study talking points and data. For the applicants and accepted, the TDMSAS broke down SES into three categories: parental education & relationship, household (wealth, household size), and hometown (inner city and rural etc.) considerations. For our conversation, we will limit our time to talk about the applicants. Lastly, those who scored more points ranked higher on the SES scale, the higher your SES rating the higher your grade ranging from SES A-D — getting an A wasn’t a good thing.

1. Is there any correlation with SES and GPA? By graphing the aggregated data supplied to us by the X, we get a graph like so:

In general, since they’ve started to consider SES there are several short term trends. Overall, over the years everyone has gotten higher GPAs however those with less SES (higher parental income and education etc.) consideration fared better in their overall GPA. The average currently shows a trend of groups SES B & C besting (higher incomes) always trumping group SES A (most SES consideration by points). Interestingly, the lowest effected by SES had the most variability in scores, however note that this group always either floats near the performance of groups SES B & C, this group also has the highest average GPA overall. In other words, there is a correlation with GPAs and SES status.

2. How is SES related to ethnicity? *We will look at the TMDSAS because of their unambiguous preferences for consideration of SES.

| *2008 Estimations to nearest whole percent.*Other races not included because values not given, so values may not total to 100% | Percent of Total Applicant Pool | SES-A (4% of Applicant Pool) | SES-B (~10% of Applicant Pool) | SES-C (~25% of Applicant Pool) | SES-D (~remaining 61% of Applicant Pool) |

| White/Caucasian American | 50% | 28% | 41% | 52% | 56% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 23% | 17% | 17% | 20% | 26% |

| African American | 7% | 17% | 11% | 8% | 3% |

| Latino American | 13% | 30% | 20% | 11% | 7% |

From the chart above we can see that the lowest SES, SES-A, only made up a measly 4% of the applicants in the 2008 cycle whereas the the top two categories (low SES score) made up over 75% of the applicant pool. Caucasian Americans (a mixture of ethnic groups) are the most likely to be in the upper two brackets, however note there are certainly Caucasian Americans qualifying for SES status — in fact, just over 1 in 4 of those with the highest rating of SES were in Caucasian Americans in the TMDSAS — as a whole this is a diverse group economically. Asians are listed as a conglomerate, from Chinese, Vietnamese to Pakistani, therefore it’s really hard to say much about “Asians” because it’s too broad of an ethnic category. Never the less, all we can really say is that Asians are also a diverse group, and should not be excluded from the SES conversation — in the lowest income bracket (SES-A) by percent alone Asian Americans qualified as much as African American applicants. African Americans and Latino Americans (another conglomeration) have the least applicants by percentage applying in the upper two (low SES scores) groups C & D, with only 3% and 7% of African American and Latino American applicants’ families qualifying for SES-D respectively. In other words, SES is a multi-racial issue and all races would likely benefit from its application.

In conclusion, the AAMC and the TMDSAS both recognize that there is a correlation between SES status and academic performance (MCAT & GPA). The AAMC also acknowledges that there is currently a disparity, or lack of diversity, in terms of the financial backgrounds of their applicant pool — this lack of diversity in the applicant pool eventually translates to financial skew of matriculates towards the upper income brackets (and parental education). In response to this reality, the SES is considered by medical colleges as a purview of legitimate holistic review. However, despite genuine efforts to diversify in this area, there hasn’t been much change in the financial portrait of students — in the next, and hopefully final article on the issue, we will discuss some reasons possibly why.

No matter if you agree or not, data is data; and it happens to be the data medical schools take under consideration.

AMCAS II Ex. 5 — What’s Your Weakness?

We are all full of weakness and errors; let us mutually pardon each other our follies – it is the first law of nature — Voltaire

During the secondary applications, there is a good likely hood that you’ll eventually hit a question that asks for your to explain your weaknesses — some questions may even have you elaborate more, some less. As premeds we’re hyper vigilant when it comes to addressing our weaknesses. The worst thing you can do on this essay is to wall yourself up, become defensive, and start playing “cat and mouse” on this question. When interviewed, this is a question interviews like to toss in, so the better you know this question the better you’ll be during it. In fact, there’s seldom a job interview that I’ve had that also didn’t ask this question (at least a job that preferred a degree).

On the other hand you may indeed be perfect, good luck explaining that to your interviews who likely can easily give you a running list of their “weaknesses”.

Here was my strategy in answering the question:

1. Present weakness (feint)

The first step to many problems is to first acknowledge you have one. (see step 3). In my example it’s my “self doubt” about past decisions.

2. Rationalize/humanize, but don’t minimize weakness (parry into step 3)

Use an explanation to explain what your weakness is in context, then project how this could be a ‘problem’ later. Pretty much, in this phase I was beating my reviewer to the punch by acknowledging my issues, then being realistic about how that is a weakness in their context as well. After that, I used that to transition into the next step, step 3. In my case I tried to reason with physicians who probably were just as neurotic as I was about things, so it wasn’t a hard argument to bridge rumination and self destruction.

3. Propose solution/plan of action for your weakness (Parry into a gentle counter attack ‘riposte’)

Up until this point, I was on the defensive as a writer, but at the conclusion I moved towards the offensive, I decided to address how I’d overcome my problem: becoming more systematic, learning how to trust and delegate better (more trust in the process less restless nights in theory). This helped turn my weakness into more of an, “Aha!”, moment then a guilty admission. The key here is to really give the “how will you solve” this problem prompt real consideration.

And the golden rule — don’t BS ( unless you believe the BS too, but that’s some type of Inception type concept that we don’t have time to cover).

—Start–

What is your weakness?

I feel one of my largest flaws is my tendency to ruminate on my past decisions. As a future doctor I could imagine myself always wondering if I could have provided a better outcome for a patient: if I just had noticed a symptom sooner, prescribed medicines more or less aggressively, if I made the correct ethical choice, and wondering constantly if there was a better way to perform my duty. This year I have strove to empirically record my observations using an online journal; it has allowed for me reduce circular worries. Later, I could assuage my concerns with meticulous chart recording and recording case studies. I should also learn how to better develop trust and delegate to others, this would help reduce a lot of stress. These skills would transfer into medicine as I better learn to foster team work with other allied professionals. While I believe self-criticism is necessary, and should be invited, nonconstructive self-doubt helps no one.

–End–

As you may have imagined, to reflect on things is healthy but to ruefully regret is not a good thing. You may have also imagined that this trait would have made me more anxious during application season, at the beginning this was indeed true. However, during that time I grew to appreciate a new philosophy about my time and how much I would worry about things.

AMCAS II Ex. 4 — How’d You Help Your Community?

As premeds (and medical students) we are expected to have performed community service. Most premeds will express the only relevant experience is something like physician shadowing or something medical. It’s a logical position, you want to do medicine so you want to see medicine; and every premed should get a taste of medicine before applying. But, serving your community in other ways would probably benefit your community than the benefit you perform for the medical team with random gopher tasks. Of course, if believe you’re doing substantial work with medical community service, then power to you — as long as you can jabber on about how you made a change you’re good. Like everything else, everything you mention is fair game for the interviews; i.e. padding your entries will back fire during an extensive interview.

I was one of those despicable premeds that enjoyed doing community service. You see as a former welfare child, long term (elementary – HS) poorly insured inpatient, and my education was funded by grants and scholarships for research I actually I already felt I owed my community more than I could ever repay. Thus I never had the “checking boxes” feeling, I was just happy to be able to check anything at all. So, for myself I suppose there wasn’t much altruism in my actions, but instead I wanted to validate my own existence and rationalize why doctors and the community kept “saving me” by adding value to myself. For my own service I decided to highlight three things and how I inclusion in the activity made a change. If you stroll to your applicant programs’ website you’ll likely see their community service, other than medical, you want to let schools know that you can contribute to anything, and you don’t find non medicine things to be “beneath you”.

My format is straight forward, I was going for a holistic application so I didn’t focus on just my medical community service:

1) Prisoner Education Program – non medical. Several medical schools I applied to have specific programs targeting inmate health. I found this out by searching their websites. It wasn’t very hard to conjure up why reducing recidivism is good for the community. It was also a great lesson in the human condition. In case you’re curious, I still did participate in the program even after I was accepted for medical school, some of my former students were released by this time, attending college and working.

2) Patient experience, medical volunteering. I had a few options, so I didn’t bother addressing my positions where I was designated pillow fluff-er (though fluffy pillows are important) or warrior filer. I instead only decided to talk about programs where I was essential (small staff) and/or that my inclusion helped their organization substantially.

So, without further adieu, my entry is below.

How’d you help the community?

I try to have an impact to all my commitments, including: civic duties, medical volunteering. My work with the Prisoner Education Program allowed me to help mentor nearly 80 adult convicts for a multistage education and job skills training program. These 80 males graduated the phase of the program with new skills vital to their later independence: job interview skills, educational advice, GED training, and math tutoring. This program was designed to reduce the statically likely prisoner recidivism by empowering them through education and mentoring. My most important medical impact was during my time helping children perform physical rehabilitation at my university’s Motor Development Clinic. I worked with two adolescents: one with attention deficit disorder and motor movement problems, and another child with extreme mental deficits who had almost no motor coordination. I worked with them over the summer, charting their progress and reporting their outcomes to the supervising physical therapist. I worked with low income parents and adolescents to improve grades and attitudes about academics, now their parents report and teachers praise the students for their improvements and their positive demeanor towards learning. Currently, I serve my community at Donuts Hospital in the Oncology department. I help children cope by providing tutoring and providing a compassionate ear to their concerns in the interim between their treatments. At Donuts Hospital I have also helped staff or organize a number of fundraisers related directly to the oncology department and children’s hospital wing.

–end–

Interestingly, my hospital work wasn’t discussed much during interviews, a lot of it instead came from my non medical volunteering. I suppose it’s not that surprising, we can assume that it’s hard to impress seasoned physicians with medical. So, although people in premed sometimes seem to hate to hear it, it’s often a strength to be different if you can justify it.

As a future physician you’re proving in this entry that you have not only done community service, but you understand why — admittedly the last part is harder to verify.

AMCAS II Ex.3 — Project 10 Years Essay

Along the way through your secondary applications you’ll hit a “Project to the Future” question in some incantation. This was one of my favorite prompts to reply to, it hopefully it will be for you as well. I know it sounds like I speak blasphemy to even imply applying to medical school can be fun, but honestly there is are some satisfying parts to the process. This prompt happens to be one of them. If you put this prompt into context, up until now you were just a premed scrabbling across the prerequisite and MCAT mind field. For a lot of applicants, this is the first time you’ll have a moment to realize that you’re actually applying to medical school (bravo you!). Now, this question should get you thinking, “Just what am I going to be up to in 10 years?”. It’s a fun question, imagine yourself with your white coat freshly pressed to get the vomit out, but it’s okay because you’re a doctor!

Also, don’t worry too much about i you’ll change your mind about your specialty; most people change their mind anyways. Though, you do want to have a tone of keeping and open mind or being flexible while driven. Make sure to check the school’s website for more specific information like how their institution can fit into your projection.

For the things I tried to catch in this entry were:

1) Involve the school and their abilities into my projection. There’s a cat and mouse game of BS between some applicants and admissions. My advice: don’t play the game, find legitimate reasons why going to that specific program is a plus. Don’t go into detail about the school, you’ll have another essay prompt to do that; instead just remember the school and you are intertwined after acceptance.

2) Show what you know about medicine here. I decided to project the imagery of me becoming a doctor. I suppose the only thing you have to worry about is that your 10 year or future projection makes temporal sense.

3) Remember that you’re selling yourself here as well, so remember that you need to sound like you’ll be an asset to medicine later. This doesn’t mean you need to cure Amyloid Lateral Sclerosis or cancer (though I hope you do), you should acknowledge the little victories in a physicians life — and I do mean little victories.

4) Remember that you will be asked this again during the interview, and maybe even expected to elaborate on several points. Interviewers who have access to your entries and their notes to them tend to ask really good follow up questions, at least that was my experience. During the interview, if your secondary was genuine then that can be pretty out-right fun; if you pulled it out of the ether then it’s down-right miserable.

As a future alumnus of Cookie Monster Medical University I see my medical career being devoted to serving the local and national community. As a Awesome-ologist attending I would help promote positive patient health outcomes by collaborating with a team of medical professional. Although I loathe the disease, I would enjoy the long term relationships I could develop with patients, allowing me to holistically treat the individual. My undergraduate research experienced combined with new experiences during medical school would prepare me for interpreting new research to be used with my patients. I would stay involved in the local community, working with other physicians and health professionals to encourage preventative screening of cooties for the under-served population of Honeybunville, empowering individuals through knowledge. At the same time I’d support and mentor residents and medical students, passing on the lessons given to by my predecessors. I have a strong belief in the link between research and medicine so I would like to get involved in clinical trials, as drugs studied at the bench are later medicines to be dispensed by a physician.

–end—

Note, in case you’re curious I did notice, “promote positive patient”, that is “P.P.P”. I sort of had contempt for the fact that I had to use those words in lieu of saying “I like to help people”, so I decided to make it almost acronym like to make both I and the reader feel better about the cliche term — I live on the edge. =D

AMCAS II Ex. 2 — Diversity Question

di·ver·si·ty

diˈvərsitē,dī-/

noun

- What do you know about diversity?

- What is your understanding what diversity means in the current medical age?

- How do you tie that together into an argument of how you’ll help better that medical program?

- I found it difficult to brain story what makes me” diverse”. This is only natural, I speak English fluently as a native, but when someone asks me to say something “in English” I can’t think of a thing. So, instead I brainstormed the tangential answers by pretending I was addressing a future patient who misunderstood me, thinking I had nothing in common with them. I then tried to think how I’d assuage their concerns, then it was easier to shift gears into how writing about my “diversity”.

- Do not confuse this with the “hardship essay”, though your diversity may contain hardships that in fact make you diverse.

For my own diversity essay, I tried to take advantage of the changing medical landscape with the Affordable Health Care Act, allowing current events to segway into my understanding of diversity was easier for me (it almost gives you a skeleton to work around). Though, the caveat here is that you have to be up on your world and national news to play the part once you arrive at interviews (better start listening to Al Jazeera and NPR now). For myself, growing up without healthcare had an enormous impact on my quality of life, after all when you have a big family you have the unfortunate consequence of seeing ‘statistics’ play out as you’ll see in my diversity essay:

A physician must interact with patients across a large spectrum of income classes, a large swath of patients live in poverty. Therefore a doctor with a diversity of experiences may be better able to adapt to this fact. Lack of affordable health insurance inexplicably leads to overuse of emergency rooms, I know first-hand as I wasn’t privy to having a primary physician as an asthmatic who couldn’t afford insurance. I can only imagine that with the passage of the Affordable Health Care Act the diversity of patients seeking treatment can only increase. Being one of *14 (two dead) I’ve seen that diversity first hand having: a brother diagnosed with HIV, one dying after chronic cocaine abuse, and a brother currently in prison. To better get to know a diverse population I have spent time working with myriad of individuals from prison as a mentor, lecturer and tutor. As a volunteer in children’s oncology department I learned that compassion is a component of professionalism. Furthermore, I am gaining a greater understand the research process as an IRB/ACUC member. As an IRB member and Ethical Compliance Officer I weigh risk versus beneficence in order to protect special populations (prisoners, children, mentally disabled, and pregnant woman) from dangers of irresponsible research: misleading informed consents, conflicts of interest, manipulation and undue influence. I believe my diverse background will create a solid foundation of experience as a medical student and practicing physician.

–end—

It’s likely that if you’ve gotten this far, you have a story to tell. So, be assertive and tell it.

*In case you’re curious, for myself, I currently no interest in children nor having a huge family. For now my houseplant named, Fernando, makes a good son.

AMCAS II Question Ex.1: Why This Area? — My Example

If you’re currently applying to medical school, you’ll likely soon start to receive secondary applications, congratulations on making it this far. Please pay particularly close attention to your first couple of secondary applications, you’ll be able to use the husk but not the heart of essays you’ve already written from other institutions. Also, during the beginning of this period, it’s easy to rush things out the door and wish you hadn’t afterwards. So, before we start I’ll remind you to proof read for typos and word transpositions (this will happen if your word processor auto corrects). Also, most importantly, make sure to never make the mistake of confusing one school’s content for another on an essay. To help avoid these mistakes use your friend Control + F to find your mistakes quicker, then print out the real secondary. Take a high lighter and lots of coffee, and make sure you don’t misidentify a school and caught most grammar and typos issues. On your computer I suggest that you make a folder called AMCAS Secondary Entries, make sub folders for each school and place their secondary essays there. Inside the main folder, AMCAS Secondary Entries, keep an Excel sheet to keep track of what types of essays you’ve written already and the character length — this will help you to make a strategy later when you’re exhausted and can’t imagine writing yet another secondary.

How to handle the “Why this area?” question

There is probably a plethora of reasons you want to go there, most of them are hopefully genuine. From your genuine reasons, pluck from them the reasons that best align with the mission and strengths of the program and their surrounding area. Also, you can tailor this entry by doing background information on the school and who they intend to serve — if you’re admitted, these are the people you will be serving. When you see similarities between those you will serve it’s a good thing. Note, this cuts across class, race and gender. What you’re trying to do in this entry is convince them that if you’re admitted you’ll be happy about your choice, and you gave it some thought. While it’s true that from the applicants’ perspective any medical school is good as long as they are accepted, The reciprocal: all accepted are good for the medical school, that is not necessarily true. In other words, a school will not invite you for an interview if they feel you haven’t really given it thought of why you want to be there — and that’ll either be obvious in this entry or during the interview if invited. Here’s one of mine:

A mentor once taught me that insensitivity makes arrogance ugly; and empathy is what makes humility beautiful. If accepted, my new mentors will forever craft my philosophy as a future humble physician. For this reason, I chose Meow-Mix Medicine School (MMMS) because the school’s core values of excellence, collegiality, and integrity. I believe becoming a medical scholar, in a new community, will prepare me for a successful career as a physician and advocate for the underserved.

MMMS integrates science theory and medical practice early; this is reflective in the school choosing to concurrently teach the basic sciences and the principles of medicine. MMMS hones medical student’s clinical problem solving skills by integrating the basic sciences patient care through small groups. My own experience in electrophysiology lab, and leading small lab discussions on preeminent research and physiology, taught me that often the best way to learn was to correlate theory with application via experience and in-depth discussion with mentors and peers. MMMS learning style encourages collaborations between training physicians; I believe this learning environment will foster excellence in the student body, as delivering stellar health care is a team effort.

MMMS keeps its medical scholars connected with the local community by providing comprehensive healthcare to vulnerable subjects by providing free health screenings to the local Kitten community at the Meow-Mix Area Health Education Center. A family shouldn’t have to choose between food and proper medical treatment. Additionally, I find it encouraging that MMMS has strong patient advocacy for underserved populations through organizations such as the Meow-Mix Meow for Health Program.I believe MMMS has a strong emphasis on patient beneficence without discrimination. MMMS commitment to the community, research, and education will prepare me for a life of service as a physician.

This the longer version (recall that you’ll different schools have different character count requirements), and experience with writing a bunch of these will allow for your to better tailor your entries. I found all of the information by data-mining (stalking) the medical school: checking their Tweets, blogs, Facebook entries, Youtube. Even if a school is huge, the department medical school PR “concept team” is usually rather small and intimate, so sometimes being the only person who watched that “wonky” video with 200 views puts you ahead of the pack. Of course I looked at their website and MSAR, but that’s sort of a basic requirement nowadays. By the time I wrote the “Why Here” essay I knew so much information about each school and area that it actually made the decision of where to matriculate to an arduous one because I taught myself to love each program I interviewed.

Note: there’s a good chance that I changed the name of the university for mutual privacy, or the proper nouns I used really exist — equally likely =D

My Primary Entry Samples

Recently people have requested that I upload some of my primary entries. That was a little harder than I imagined, most because I sort of jettisoned the whole primary application from my life after I was accepted (sorry, didn’t know I’d be blogging). Luckily, I’ve found my copy and I’ve copied a few of my entries below. You may notice that I redacted some information for my privacy. Besides that, and typos that may appear from me having to copy and paste it a few times to here, these are some of the primary entries I submitted. Next week, I’ll post some of my secondary essays.

Clubs / Hobbies:

As you can see from my hobbies, or lack thereof, I didn’t have much going besides academic life. I personally enjoyed the world of academia, and I’m still involved, so I had no shame in being upfront about my “lame” hobbies. Like many premeds, I learned to trick myself to like the nerdier side of things. Give me some books, lots of paper and a writing utensil, and then I’m satisfied for life. Though, I do own several guitars I haven’t actually sat down and properly practiced in years, that was my only note worthy hobby. However, since it was something I hadn’t done in a while, I just chose not to bring it up — just in case my interviewer decided to have a guitar solo battle to determine my eligibility. =)

| Clubs / Hobbies | |||||

| Experience Type: Hobbies Most Meaningful Experience: No | |||||

| Experience Name: Clubs Dates: 09/20XX – 06/20XX Total Hours: 360 | |||||

| Organization Name: Waffles University | |||||

| City / State / Country: Waffletown / / United States of America | |||||

| Experience Description: University Tutor Club (Sept.20XX-present): volunteer tutoring to students who otherwise could not be tutored because of Waffle University. Traveled to Stanford University to lead a meeting regarding Organic Chemistry best tutoring practices in 20XX. Also participated in annual budgetary hearings where I successfully petitioned for an increase of funding for tutoring. (30 hours) | |||||

| XXX Research Scholars Club President (Sept.20XX-20XX): responsible for fundraising, mentoring Upward Bound students interested in the sciences and pre medical degrees. (80 hours) | |||||

| Human Physiology Research Journal Club (Jan.20XX-Nov.20XX): club focused on discussing and presenting weekly assigned research journal articles. In this group, I was expected to present an hour long presentation at least twice a month to critique the methodology and scientific merits of studies focusing on muscle and neuronal excitement. (250 hours) | |||||

Experiences (not most meaningful entry):

To enter this section, I just took my working Curriculum Vitae and resume, and crafted them to fit the AMCAS style/character count. One of my main strategies was not just to list what I did, but try to explain why it’s important that I bothered to mention it at all. I should note that I didn’t use all of my entries, I think I used about 12 of the 15 — I don’t like filling up space if there’s nothing to say.

| Experience Type: Research/Lab Most Meaningful Experience: No |

| Experience Name: Research Assistant Dates: 06/2010 – 12/2010 Total Hours: 60 |

| Contact Name & Title: Awesome McAwesome, Associate Professor |

| Contact Email: aawesome@waffles.edu Contact Phone: |

| Organization Name: Waffle Univ. Biological Department |

| City / State / Country: Waffletown / CA / United States of America |

| Experience Description: I conducted a proof of concept sub-study for our lab, to demonstrate that action potentials (APs) in muscle can be measured using the electro-potential sensitive dye Di-8-ANEPPS ((4-{2-[6-(dibutylamino)-2-naphthalenyl]-ethenyl}-1-(3-sulfopropyl)pyridinium). Similar to the mechanism that makes fire flies glow, Di-8-ANEPPS emits a photon of light when electronically excited. After dissecting out the muscle I would then integrate Di-8-ANEPPS into the muscle membrane, where it would excited. To measure the correlation between intensity with the magnitude and density of excitation I selectively blocked ion channels florescence when the muscle fiber was electronically. |

One of my most meaningful entries:

This is one of my most meaningful experiences. I choose my most meaningful 3-entries in effort to show balance. One entry was about research, another was on my experience as a volunteer in the correctional system, and the last was about my experience with patients. I felt I had to be strategic about displaying that I could fit into medical schools’ holistic views.

| Experience Type: Research/Lab Most Meaningful Experience: Yes |

| Experience Name: Co-Principal Investigator Dates: 01/20XX – 11/20XX Total Hours: 999 |

| Contact Name & Title: AA Awesome, Associate Professor |

| Contact Email: aawesome@waffle.edu Contact Phone: |

| Organization Name: Waffle Univ. Biological Department |

| City / State / Country: Waffletown / CA / United States of America |

| Experience Description: I started the project by performing a comprehensive literature review, and creating a muscle electrophysiology timeline in neonate and adult mice. This timeline was presented to the lead investigator, and used to justify our need for animal experimentation to the Animal Care and Use Committee. From this project I was selected as a XXX Research Scholar, helping to fund my study. This opportunity allowed for hands on learning of physiology. After nearly two years of work, 20-30 hours a week, I was able to present the project at UC Berkeley in 20XX. |

Hope this helps!

Secondary Tips Part 2

“I didn’t have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one instead.”

― Mark Twain

I’m sure Mark Twain would of been great at Twitter. If you’ve used the social network platform Twitter, then you’re probably already grown accustomed to distilling your several page treatise on why “Slovenian desserts are the best” into a succinct 140 character tweet. Now, I know what you’re thinking, “These youngsters are hacking up the beautiful English language with their Tweets, texts, memes, and…and stay off my lawn!”, but we have to get past that. It’s a lot easier to ramble, I’m sure if you gave a blindfolded drunkard both enough darts and time they’d hit the bulls-eye eventually; though, I wouldn’t want to be anywhere in the vicinity. And really, that’s what makes tweets and secondary essays similar: you need to take a voluminous shallow argument, shed the irrelevant husk, and distill a succinct/petite and cogent statement.

- 1# Don’t write secondary essays without a plan.

I have some ground rules that I set for myself, these helped me successfully get past the secondary process with a lot less stress. Fortunately, a lot of these skills are taught in grade school, “put your thinking caps on!”:

Plan your premises out before writing (this will often mean doing your homework).

prem·ise

noun \ˈpre-məs\

premises : a statement or idea that is accepted as being true and that is used as the basis of an argument.

If you don’t spend time developing your premises before hand you’ll soon find you’ve exceeded your character limits or alternatively, you can’t anything to say. I know it’s feels “easier” to just get cracking on the writing, but vomiting out a page is an old trick you should bury with college. In the temporal sense, it will also take you longer to “fix” a meandering essay than to make a game-plan for them. It’s a lot easier to fix a problem of ingredients before you’ve baked the cake. For each essay distill cogent premises into reasonable argument for acceptance. Once you start writing to fill in the logic between each premise you may notice gaps, or you may notice weaknesses in your argument. But, really the lesson here is, if you don’t know where you’re argument is going don’t expect your reader to know either.

Since most secondary questions are somewhat similar, there’s a big pay off to perfecting the premises and figuring out how to string them together before you start writing because some portions of your essay will be “recyclable”. For example, once you’ve hammered down a great way to explain your “Why medicine?” question, there’s no reason to revamp it exempt for individualizing the essay.

- #2 Every single secondary should be individualized.

If you’re not willing to take the time to individualize your essay for 20 schools, why should admissions out perform you by taking the time to read through 10K applications to finally find yours? Individualizing a letter goes further than making sure you drop the programs name in the essay, it means getting to know the program. The more you know about the program, the easier it is towards their needs. To do this, spend sometime investigating each program you applied to. This will have a huge pay off when it come time to interview, because you can just re-use and continue from where you left off on your notes. For example, in the “Where do you see yourself in 10 years”, like essays it’s important to know what areas your school is serving, so that you can project yourself in that area.

For each school, start by doing your home work, and chart your progress, so you can easily compare and contrast programs. If you receive interviews or multiple acceptances this will be valuable. It will also make writing secondary essays easier, if you already know what information you can individualize. Keeping track of the schools blogs, tweets, and news in their local paper helps a lot with this.

Take a look at my example below, and start doing your homework.

| Institution | Mission Statement | Location | Cost (CoA) | Student Body | Teaching Style | Pros (opinion) | Cons (opinion) | Links/notes |

| University of A | Something something we love research. | rural | 93,000/yr | ~200 | Problem Based Learning | Heavy research, and I have resarch exp. | Resident match was mostly local only; costs. | youtube links, their blog page etc. |

| University of B | Something something we are a community driven program. | inner city | 62,000/yr | ~100 | Traditional Lecture, mandatory | Costs; takes advantage of my past CC involvement | Little institutional research; and mandatory lectures. | Their underserved community is X city per their blog. |

See part 1 of this article:

https://doctororbust.wordpress.com/2014/06/16/preparing-for-secondary-applications-part-1/