medschool

Half Way Through MS2 – Studying for Boards

Hello,

From Boston, happy autumn! Here’s a picture near my house.

Around this time of the year, squirrels should have already built their nests, and premeds are getting interviewed at medical schools. Third year medical students no longer exist, and fourth year medical students are taking care of their residency process. For me, I’ve just past the midway point of my second year of medical school and board examination. A few weeks ago, I started to prepare for the boards. When people decide to prepare for the boards is up to them, each medical school gives their second year students time off before their examination to dedicate their time to it. However, due to the high stakes of your permanently recorded score, must students start preparing for it earlier — some students have started studying since last year, some started this summer, the large majority seem to wait until fall or winter to start thinking about it — it’s a personal choice when you decide to start it. For myself, I have a hard time evaluating what I do and do not know, so answering questions works for me whilst taking the same course: I do psychiatry questions during the psychiatry section of class. In essence, I’m trying to eat my cake and have it too, I’m trying to use the boards as an adjuvant to class or vice versa.

If you’re not familiar with the boards, and most notably the question style, this succinct best flow chart below explains the situation the best…

Here are the resources (besides lecture material) I use, so far:

- Goljan (high yield notes) – there’s a mix of materials, written and audio, you can choose what works for you.

- Board Review Series (BRS) – I supplement this when needed. The lecture notes will be more detailed, but BRS is best used IMHO to get the big picture.

- First Aid (notes) – I’ve started to just take notes straight into it. When I get questions wrong (any question bank), I just look up the topic in First Aid, see if it’s a fact that I never heard of or not, then I finally just annotate straight into the book.

- Sketchy Medical – this is a must have for all second year medical students. You will feel absolutely ridiculous using this in public, but your blushes are worth the pay back. I watched the videos and used the provided PDF ‘images’ as Anki (flashcards). Thankfully, they’re coming out with a Pharmacology series, I will definitely pick that up.

- UWorld (question bank)- the school strongly suggested we just stick to UWorld and some other materials they’ll update us about later, they also told explicitly told us to avoid a certain company. We were told they ask the appropriate level of third order question that we should see on our boards. I started with just doing 3 UWorld questions a day, I started only within the same subject as I was learning. Now, I do 6 in-subject and 4-5 previous subject questions. Afterwards, I just review what I got wrong and annotate that into First Aid.

- Anki – I’ve used it intermittently. It can get sort of boring to do, but it does help a lot if you just have to remember a lot of details. For myself, I’ve learned the simpler and less “busy” the card the better and faster I’ll memorize the card duo. The trick to making Anki useful is to speed up the rate it takes you to make cards. If you have a diagram, table, or image to memorize then use image occlusion. To my knowledge, and at least on my Mac, image occlusion is either missing or obscured away in the Apple compatible version. If you’re using an Apple, then you can install Wine. The Wine program will allow you to run windows programs on your Mac. If you design a two-item table in Excel (both Windows and Mac), then you can save it as a .CSV. A lot of people don’t like using Anki because it takes too much time to make cards. I remember, in my first year I’d spend hours making cards, now it only takes about 20-minutes to do the same amount of work to make them. For me, it was just important to not try to make a card for every little detail and not lose focus of the medium and big picture.

- Doctors In Training (DIT) – I just received a confirmation order, and I should be receiving it soon. I’ve heard very positive things online, especially last year when second year students were tweeting about their board results. When I get some time to sit down with it, I’ll update this blog with a review of how it worked for me.

- Pathoma – it seems like I’m the last person in my class to use this, but I just started to try it out this week.

- PubMed – often, a handful of lectures can be summed up by a short well written paper.

Anyways, that’s what I’m doing for the boards. I really don’t like adding new things into my study schedule — the more wonderful the tool the more time it usually takes to learn how to use. For this, I use First Aid as my nexus of information by taking notes into it. If I see an article on PubMed that explains it the best, then I write down a couple of words plus the PMCID so I can look it up later. So, for any source of information (especially when using multiple) I find it’s important for me to keep good track of references. I’ve even found it useful to cite First Aid pages within First Aid itself, for example at times where two concepts go together seamlessly (in my mind). If you’re in the gallows of the first year, hang tough, when you finally figure out how to juggle flaming sharks as a MS1 you’ll be able to transfer a lot of the skills over to MS2.

I use my course grade as a barometer of how well I’m balancing my position as a medical student, research, volunteering (mentoring), shadow, clinical duty, board studying, and personal life. To pass each module you need to have an average equal or greater than 72%. This year, I follow the suggested set-point given to us by our academic advisors, I try to keep my average around 85% — I’m willing to miss a few points on a written exam if it means doing the things I like. Anecdotally, I’ve heard striking a balance is key:

- I’ve heard of a minority of students going hard on board studying, but neglecting the grades, and they had to remediate courses and lose time studying for boards anyways.

- I’ve heard of a minority of students going hard on course work (nearly achieving perfect scores), not studying for the boards until the last minute, and ultimately having to retake the boards to get a score a more representative score.

- On the flip side, I’ve heard of a smaller minority who by virtue of doing nothing else but study successfully destroy the boards and the coursework, but then had to take a gap/research year to become more competitive in terms of extracurricular — this is obviously a very specific case, and really only something worth thinking about for extremely competitive specialties. Though, in the scheme of things, this is the best of the three problem situations to have.

Anyways, have a great weekend!

Last Hospital Shift of the Year

Hello Everyone!

Happy holidays, I’ll be ringing in my last shift (possibly, unless I get the itchy urge and find another slot) of the year in the ER/Trauma tonight. Tonight’s ‘uniform’ will be white coat and scrubs (also known as medical pajamas).

Doctor: can you guys call the other pharmacy to verify their prescriptions, dosage, and amount? If you don’t understand what they say ask them to repeat it.

Other medical student and I in unison:….sure…

Medical school is interesting because you cross the line of your comfort level a lot, for me it was a simple phone call. Everyone has seen the gibberish on prescription bottles, it’s a niche language, unless you mother tongue is latin I suppose. At my level of, without any pharmacology coursework, you might as well be speaking dolphin if you rattle off drugs to me. Anyways, it was a mission accomplished after googling the pharmacy and boasting my best competent person impersonation to the pharmacist over the phone.

The line between being a fly on the wall and becoming part of the process is ever blurring, even if it’s in the most modest of ways. For the surgical residents we stayed with making phone calls was probably the most trivial part of their day.

In class updates my neuro exams were yesterday, so academically I’m done for 2014! The verdict? Neuro is going a-okay according to my exams. Last semester’s medical biochemistry gave many of us quite a pummeling (even biochemistry majors), so I’m trying to learn from that experience and make improvements in how I approach studying for medical school — if neuro is any indication I’m headed in the right direction.

In physician training news we start giving physical next year (January 2015), upon admittance some generous alumni paid for all of our medical equipment:

After further work with real patients, for the first time, we’ll be exposed to a standardized patient to evaluate/grade our proficiency. In the meantime I’d rather not torture patients, so this month I’ve been volunteering my friends to eye and ear exams — incidentally, I never noticed how intimately close you need to be for eye exams:

I won’t be traveling home for holidays, I’ll just hang out in Boston instead this year. In Boston a large chunk of the population are students, college students at that, so plenty of people leave this city this time of year. As a consequence, a lot of my classmates have flown home, while some like me are sticking it out here. But, I’ve already made my agenda for how to spend the vacation:

1. Blog a little more (not to be substituted for sleep), hopefully it’ll be helpful for premeds

2. Go to favorite jazz bar several times, possibly with other people (haha)

3. Sleep

4. Experience Boston Christmas experience

5. Skype with family

6. Oh yeah! Wash white coat, this thing attracts stains

*7. Take time to appreciate the volume of information I just absorbed, won’t be studying, but I will bask and reflect

I wish everyone a happy holiday!

Neurology Midterm Over!

Hello,

Finished part of neurology, the midterm was worth 30% the final will be worth 70% of the grade. The course is split up between lecture, lab, and discussion (electrophysiology). The lecture portion of the course only started a few weeks ago, but we’ve already covered several hundred pages, between 1500-2000 slides (120-180 new slides per day), and several hundred more pages out of the text if you found time to do that as well — I should note that of the 120-180 slides you’ll probably only receive 1-3 questions, so you study everything in the hopes that you might understand it and hopefully see that concept on the test. In lab we dissect the brain we dissected out from gross anatomy, it’s a good break from lecture and requires less brain power than participating in electrophysiology discussion. So, you might be curious what learning neuroscience/anatomy is like. Well, the easiest way to understand it is the example below:

In the ball above, imagine your were given the task to find out where each rubber band was going. This also means knowing where each rubber band was crossing another band. Now, imagine each rubber band has a function, so you’ll need to know that too. And now, imagine you weren’t allowed to take the rubber bands apart, you’re forced to make a 3D map in your head instead. That’s medical neuroanatomy.

So, medical neurology/anatomy comes in several flavors. Some questions give you an amorphous blob and you’re expected to make sense of it:

A typical medical school question in neuroanatomy is a second or perhaps third order question, they’re doing you a favor if they ever ask you a first order question. For example, it’s rare that you’ll be asked ,”What is structure L?”, instead it’s more normal to ask “Where do the axons that originate in location L?”, or, “What symptoms would manifest in a lesion of structure labeled L?”

From the lecture material we receive many vignette style questions, also known as mock board exam style. If you’re not familiar with a vignette, it’s just a short story that leads into a question. Some of the story will be useless some of it will be useful, it’s your job to figure out which is which — it’s not far off from how real cases tend to be. A typical style question for neurology is:

“A 53 year old right handed bartender comes in after insistence from his wife because he’s been tripping more than usual lately. His pupil reflexes are intact, and he’s orientated in time and place. The neurological exam was unremarkable, except that his reflexes were exaggerated in his left leg. You also notice that he stumbles to his left when you ask him to walk with his eyes closed, this only happens when his eyes are closed. In general, what lesion would explain his symptoms?”

A. upper motor neuron lesion, right posterior spinocerebullar

B. upper motor neuron lesion, left posterior spinocerebullar

C. lower motor neuron lesion, right posterior spinocerebullar

D. upper motor neuron lesion, left rostral spinocerebullar

E. upper motor neuron lesion, left ventral spinocerebullar

On the upside, the questions are interesting and you start to feel all doctorey! Now, I feel a lot more prepared to attempt to understand when a patient comes into their appointment with a constellation of symptoms not easily explained away. Presumably, now that I just learned a bit of neurology I’ll think every patient that comes in has a neurological problem — I also assume I’ll think the same way for each system that I learn about. I suppose it may even sound a little silly, but it’s funny how the symptoms you learned just but a day or two before become relevant when that patient walks in the room. Sure, you won’t see that 1/100,000 diagnosis, but you will see stroke survivors and those with lifestyles that all but summon an impending cerebral accident. So, neurology is tough, but it’ll be the first time in medical school medical students will start to think like physicians.

Gross Anatomy Resources & Tips — Warning, You Can’t Unsee This Post

Hello All,

So, a few weeks ago I finished Gross Anatomy, yay! This course is very time consuming, but interesting as long as you don’t mind smelling of formaldehyde and having bits of human flesh on your your clothes or exposed skin from time to time. In this post I’m going to share some tips that helped me get through. But, be fair warned, some of the links I’ll post are extremely graphic so view at your own discretion — some may even find this post somewhat traumatizing. If you’re not in medschool yet then these tips may seem hard to understand, but trust me once you’re there you’ll get what I’m saying. Your medical school (or future school) may have a different setup or variation, but here was our schedule for 3.5 months:

Written Test and Practicum

Unit 1 – Back and Limbs & Osteology (bones) Study & X-ray

Unit 2 – Thorax, Abdomen, Pelvis Cross Section (CT scans or cross sections)

Unit 3 – Head & Neck (Osteology, X-ray, CT scans)

Back and Limbs — Specific Tips

Initially, I had a pretty rocky start with this course, my roommate (also a 1st year, but at HMS) also lamented on the difficulty of “Back and Limbs”. But, really the hardest part is just figuring out how to study for the course. In retrospect, the material is rather manageable, but this is only because you get better at the skill sets you need to do well in Gross Anatomy.

– Be familiar with the acronyms. Back and limbs isn’t conceptually difficult, after all you probable didn’t need to go to medical school to know that you had an elbow. However, what does make it hard is the jargin, and depending on the staff you’ll hear more or less of it, in our case it was taught by someone who loved ortho so listening to their lectures was like listening to someone read out what they saw in their alphabet soup. This actually was probably the hardest part, try drilling these acronyms they use as quickly as possible so you can mentally join the discussion.

– The brachial plexus will be your first arch nemesis. At first, it really does suck, but it gets better trust me. However, it mostly gets better because other things you encounter are worse (evil cackle). You should must feel very comfortable with the brachial plexus, especially as it’ll show up on Step 1 (your board exam for MD and optional for DOs who often take their exam and Step 1). Interestingly, expect to get a lot of questions with the stem “Someone was stabbed at a bar, now they have this symptom, which nerves may be effected?”

– You must feel comfortable with the arterial and venous supply in this section. The best way is to draw them out in any way you see fit, as long as it’s accurate, then check with your trusted friends, TA, or professor to ensure the accuracy — there’s no point in studying something wrong. Lymphatics often isn’t very emphasized in this section, at least for us, but it was in the other sections.

– Osteology, what can I say, don’t forget the bones. Knowing the bones become more than a didactic exercise once you see a X-ray scan and are made to predict which muscle would be impaired.

Thorax, Abdomen, Pelvis — Specific Tips

– The thorax is rather straight forward, there’s a heart, lungs, a few nerves running through it and some vessels surrounding the ribs. You should feel confident about cardiac cycle (including fetal), and know the embryological origin of all of the heart and it’s associated vessels. The lungs aren’t bad either.

Pelvis — the bane of most 1st year’s existence. This video will help a lot!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pbCdR1PumnU (not graphic)

– Go to lab frequently, don’t be afraid to get eerily close to the dissections so you can find obscure structures. Most people struggle with the pelvic floor, the layers, and what can articulate with what. Lymphatics are tested heavily in this section.

– Lymphatics are important in this section because they let you predict the spread of cancers — as a consequence, you should also be familiar with collateral blood flow so you know what happens if you were to remove that diseased section.

– If you need to read CT/cross sections, start building up your skills early in the course and you might actually learn to like this portion of the course. The easiest way I found was to start with one structure, for example the superior mesenteric artery, and trace it up and down (rostrally and caudally, or even medially and laterally). Going to lab, doing practice questions, and looking at scans are a great way to build a 3D image of the body in your mind. For cross sections I strongly recommend RAA Viewer

http://bearboat.net/RAAViewer/RAAViewer.html (graphic)

– The intestines look like what they should only when they’re correctly placed in the body. After your dissection and during the test expect them to be in the silliest of positions, so get used to identifying landmarks to find your place as soon as possible. For example, the spleen or liver are typically the easiest to find, if you find those you can immediately orientate yourself. This also goes for the heart, you should be fine with seeing the heart in any position — don’t just practice in perfect positions, challenge yourself.

Head & Neck — Specific Tips

– The bad news is that this is probably the hardest section both in terms of dissection and identifying structures. The good news is that if you’ve been working hard in the other sections all of the skills you’ve previously acquired will come in handy — you’ll need to just have faith in that.

– Most of the had and neck is quite manageable, though you might feel differently once you get to the back of the pharynx. The key to this is to drill the section with friends, and videos like this help:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ER0nI__ZrQ (Acland video, graphic. Also, search Acland on Youtube for more sections, especially heart development)

– You should be very comfortable with seeing the head cut sagittally (split between the eyes), or even a coronal cut (typically from a CT scan). Learn the sinus drainage, and be able to identify them in both of these planes.

– The trigeminal nerve is tricky, the best way to get to know it is to draw it out over and over again. Then, in lab while studying try to answer what would innervate this, what would a lesion manifest as etc.

– Don’t forget about development! It’s not that bad, there’s a lot of easy patterns that you’ll notice if you study them early enough, e.g. pharyngeal arches 1,2,3,4,6 (that’s not a typo) will develop into CN V, VII, IX, X (superior laryngeal), X recurrent laryngeal etc. That may sound tedious, but trust me, if you’ve made it this far you’ll probably know how to remember random information anyways. The key here is to make sure you drill what your school considers important, typically innervation is a skill you need to have.

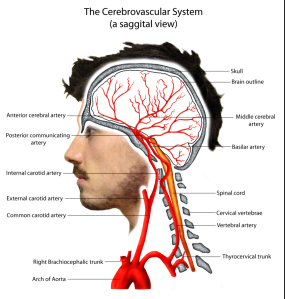

– You must be a pro at certain things like cranial nerve lesions (aka memorize it cold). Also, a very repeated theme so far has been the Circle of Willis. This structure is important because cerebral accidents (clots etc) here are often disastrous. Be ready to identify each branch of the Circle of Willis and all of it’s immediate tributaries and confluences, it’s very important to be able to recognize the branches of the circle in different views as CTs can be rotated and given to you at any angle (just know the major views discussed in your course). You should also have a general idea of, where the arteries that make up the circle, this will probably be covered more in your neurology portion of your courses — having a good 3D idea of “what is next to what” will help in the written section when you need to eliminate wrong answers based on knowing a few clutch details and it makes the skull a less terrifying place. This site has a great key of what you likely need to know.

Here’s a link, you probably should also check out the other videos! This one in particular is of the infra temporal fossa (somehow my favorite section):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g7vUXNc9lrc (very, very graphic, I’m not responsible for your nightmares! If you’ve never done Gross Anatomy these videos will likely change your life.)

Overall Tips

– Gross dissection and studying are often disparate things, so don’t think just because you’ve scraped away all of the fat in the ischioanal fossa you’re pretty much done with the pelvic floor. There’s skills that you’ll gain in lab that’ll make dissections easier: loading scalpels, findings nerves from a rat’s nest, skinning etc. But, when you’re studying it’s a different mindset. Instead, go to lab with friends (try not going alone, if you’re the only one there it’s seldom productive) or join a group who’s studying and quiz each other/teach other. The more you go to lab, way before the test, the easier the practicum will be — once you get better it’ll also translate into your written scores as you incorporate more theory into practice. Of course, this doesn’t mean you should neglect your lab duties and screw over your teammates either, instead try to come prepared by knowing what’s important to look for during dissection so you can get out of lab as early as possible — for this it helps to show up to lab 10-15 minutes early and look at some examples (if your school has them), ask the TAs for tips or things to watch out for and you’ll be in much better shape.

– One of the biggest difficulties of Gross Anatomy (hell, all of medschool at the get go) is the language. Yes, you probably can process what it means when your professor says “It’s dorsal, yet slightly caudal and lateral to the cavernous sinus”, but if it takes you too long to stomach the lingo you’ll be out of luck because by the time you’ve translated they (your professor) has moved on. Likewise, learning some of the roots of the words, or conventions, makes things easier to remember — for example, the pudendal nerve’s function is easier when you know that pudendal stems from a word referring to the “gross (as in yucky) region”.

– Don’t be afraid to be pimped, you may think you’re getting picked on by your anatomy TAs, but it’s really to help you. You’ll go from getting pimped and hating it to being frustrated because you can’t find anyone to “challenge” your knowledge by pimping you. The best way to learn the lab part of the tests, and link it with the written background, is to drill with others and figure out what you don’t know.

– Bring a “dirty notebook”, a notebook and pen that you don’t mind gets greasy from human fat or intestines etc. When you go to study or during reviews, jot down what you didn’t know or misidentified as a “to-do list”. Have someone knowledgeable help you find items on your “to-do list, don’t forget to ask how they find it so you can do it on your own too. Next, go find those structures on at least 3 other bodies. For one section I went gun-ho and did almost all the bodies, it was by far my best section.

– Attend every speed review your school hosts. If your school doesn’t have one, or only does a speed review for the 1st section etc., then get together with your classmates to run your own. It’s tedious, but making a few people into resident experts in certain areas (the orbit, the neck etc.) and then helping each other is a good way to save time and learn more. Once you’ve seen a speed review you’ll know what I mean. But, above all else remember that a speed review isn’t to teach you, it’s to let you know what you don’t know so you can go work on it.

– Make sure to ask your predecessors for tips, they’re usually more than willing to save you the pain they encountered.

– Atlases: atlases are important for references and understanding of relationships, e.g. which arteries branch of what other arteries. But, keep in mind that the body will do whatever it feels like and so will often violate a pristine Netter Atlas drawing, this is especially true once you enter the abdomen and pelvis. So, an atlas is a great supplement, but it’s not a replacement for getting dressed in scrubs and heading to lab with a probe and tracing structures back.

Most importantly, you don’t need to love Gross Anatomy, but because someone gave their body to you be sure to respect it.

First Semester of Medical School is Over — A Wounded Survivor’s Tale

“But, for better or worse, in medical school you don’t have time to really “deal” with how you feel or else things would never get done.”

Yes, it’s finally over and I get a break from medical school. I have a few days off, though I trauma duty this Friday night on Black Friday (this is more of a treat for me than anything else). I wanted to update you on what’s going on, it started off rather short post and then expanded into a meandering account of my brief foray in medicine white a short white coat.

It’s only been about 3.5 months since medical school has started, but as many medstudents would admit, looking back it feels like a year has elapsed. In 3.5 months we’ve crammed a year or more worth of graduate education. But, the course that stands out the most to me was gross anatomy. Yes, the human body is interesting, it’s probably the best example of organized chaos leading to something good.

Gross Anatomy

The poster child for medical experience is Gross Anatomy & Dissection. As a person, you change a lot after Gross Anatomy, it’s practically a rite of passage for almost all MD (and DO) candidates. I still remember the emotional experience we had the week before our first “cuts” into our donor. We were hesitant on the first day of dissection, that is to say no wanted to make the first “cut” into the person laying on a slab of lustrous aluminum table. You see, whatever excitement we had about the process was taken to another level when we learned more about the donors as we watched one speak on video about why she decided to donate her body. Seeing her, I couldn’t but help think how much I’d of enjoyed meeting her. After all, she seemed rather friendly, quick witted, and rather friendly. So, on the first day when we dissected, I couldn’t help but wonder what the woman lying in front of me was like. Did she have a sense of humor, did we like the same movies (Groundhog’s Day, or anything with Bill Murray), did she have good stories to tell? But, for better or worse, in medical school you don’t have time to really “deal” with how you feel or else things would never get done. Then 3.5 months later, we’ve done a lot more in dissection I’d ever imagined possible or feasible — I also have a lot of new funny-awkward, and likely for you, disturbing stories and sights. It’s an experience.

The Struggles

The biggest shock about medical school isn’t how hard it is — well I take that back, it feels like we’re in mental medical school bootcamp. It’s a new experience for most people in medical school, how hard it is and what it takes just to get an “average” score. No matter the institution, compared to their peers in college, most people who made it into medical school probably were on the right side of the bell curve academically. In medical school, that changes rather quickly and at best you’re like everyone else. That can either be intimidating or motivating depending on how you choose to see it. Conceptually, the course work isn’t very difficult. Instead, it’s just that you’ll cover a ridiculous amount of material in even one day, and you’re responsible for a ridiculous amount of more (but ‘different’) information the next day and so forth. Unfortunately, understanding will often take a back seat until you’ve remembered a large heaping of information that you must have ready at a moments notice for regurgitation. Then, if you’re lucky it’ll somehow all become clear before the exams, typically though as fate would have it expect it to be after the exams. I don’t have any grand stories to tell you about how to make this process easier, it’ll get easier because you’ll grow accustomed to it because of the consequences of not.

Clinic/Hospital Duty

The biggest shock isn’t the difficulty of medical school, after all there’s rays of sun in back of the clouds. Instead, it’s the level of responsibility and trust thrusted upon us. Before, as a premed in the hospital, the most that was expected and allowed of me as to perhaps fetch water and if I’m lucky bring a stool sample to a lab. As medical students, one classmate has already intubated someone under supervision, another has done CPR for 15-20 minutes until the patient was announced deceased. Besides trauma, many of us spend time with either inpatient or outpatient hospitals or clinics around Boston, I’m placed at a community hospital and clinic. I suppose my capstone experience for this “course” was when the doctor just gave me her new patient, said get “Get a health history, after that we’ll do a physical” and left the room leaving only me and the patient. You may wonder why, out of all the things I spoke of being trusted with a history is so important. Well, it’s often said that perhaps 2/3 of all medical diagnoses can be correctly deduced from a good “health history”. It’s an interesting experience, while having a conversation with a patient, you try to extract information that might be pertinent to their health. This often means you, underhandedly, lead the conversation into a direction where the mountains are rich with information. If someone comes in with back pain, you lead the conversation in a way that their history might give enough clues to both elucidate and eliminate possible causes. If you ask too many questions in a rapid fire fashion the patients won’t communicate with you, or might just eject you out of the room. For example, here’s a typical exchange with patients as I go in blindly without seeing their history:

As introducing myself, and asking a few probing questions

Me: do you have any health issues or diseases?

Patient: no.

Me: sorry, maybe I’m mistaken but when I asked about medication you said you’re taking X medication?

Patient: yes, I have diabetes but I’m healthy.

Me: oh okay (writes down diabetes)

Often a patient will just misunderstand what I’m looking for, or in this last case perhaps misinterpret the difference between having your diseased being properly managed and being free of disease. There’s insider information in medicine, just like how there’s insider information your car mechanic knows because of their trade. There’s also two of my favorite typical exchanges:

Me: do you smoke?

Patient: smoke what….?

Me: ….tobacco?

Patient: oh, NO.

Me: so, what do you smoke?

Protip: to those not in medicine, your doctor or the medical student working with you doesn’t care about what you decide to inhale, or stick into any orifice. We care about you and we care about your problems and health, but learning of your addiction to prostitutes or meth isn’t a black eye in our book, it’s simply part of the puzzle of trying to get patients healthier. Fortunately, most patients are rather frank with the drug and sexual history, making presenting and giving a differential diagnosis easier to my attending (thank you), as long as they tell the right stories and we ask the right questions. You’d also be surprised to learn that the most important part of the visit is likely the last few minutes:

Me: okay,..(recite history back to them), do you have any questions?

Patient: no

Then as I’m walking out the door

Patient: actually, there’s one more thing…

As a rule of thumb, patients postpone the most embarrassing questions for the end, i.e. genitals not in tip-top shape, or the real reason why they likely visited that day. So, during the history, if you can help get this information from them earlier you can both save time (after all there’s a waiting room full of patients waiting) and that person may even receive better treatment. Once you realize that you’re wearing a white coat and a stethoscope therefore most people trust you with it gets easier to just ask someone about their safe sex practices, depression issues, or the hue of their bloody poo. Red feces means the bleed is more distal, i.e. near the anus, whereas dark (tarry) colors infer an upper GI bleed. Red feces is typically more innocuous than darker stools, and therefore all of my follow up questions are different. If you had fresh red blood in you toilet, I’d try to ask questions to eliminate dehydration for example — but the trick is that I can’t use the word dehydration in my questioning otherwise the patient would likely just respond “No” because their definition of dehydration isn’t the same as the medical one. At first doing all of this is really hard, to keep track of things so that you can lead the conversation towards trying to obtain a differential diagnosis, but it’s fun and we’re all getting better at it and I’m sure we’ll continue to. I’ve heard amazing things about some my classmates as well, and we usually swap our horror stories or goofs.

Some days are less fun, for example being there as you watch a physician try to communicate that maybe the patient won’t be okay, that cancer has moved faster than expected. Interestingly, you’ll have to move room to room and patient to patient, while not bringing the weight from each patient with you.

Differential Diagnosis Training

You may have wondered I brought up “differential diagnosis” as a new responsibility. One thing we learned really quickly is that the peking order goes, from highest to lowest: attending, resident, medical students. But, while being at the bottom of the totem pole, it’s still a team, and you’re expected to contribute a quick witted input or two from time to time. No, you don’t need to try to diagnosis someone with Kuru, but you should be able to understand that the bladder cancer patients cancer has grown and is now likely impinging on the nerves in the ischioanal fossa based on what the patient has recently told you about pain while sitting. You should be able to understand how the patient’s refusal to take Vitamin D while still taking their prescribed dosage of calcium explains why they’ve gone from osteopenia to osteoporosis. We have a course on how to do this, we learn how to research on diseases and how to integrate so that we may differential diagnose, it’s not a set of skills you’re expected to walk into medical school with. In fact, our final exam, was similar to an episode of House (without the grumpiness) where we got a brief paragraph and lab results and tried to differential diagnose a mock patient, our tools being a white board and a few other medical students for brain storming.

Overall

So, my first couple of months of medical school has had ups and downs, a lot of difficult times and exceptional ones. But, I enjoy the experience more than I’d ever imagine, because if anything my worst fear is abated: I’m never bored in medical school. As a classmate said today after we finishes our first semester, “I feel like a different person than when I started”.

Still Surviving Medschool

“Success is a lousy teacher. It seduces smart people into thinking they can’t lose.” ~Bill Gates

As of late, like the other thousands of medical students in the country I’ve been busy. Too busy to even post as much as I’d like, but here are some updates on what medical school life is like for me. I’ve recently just finished battery of tests.

During orientation week we were told “A lot of you will fail exams and classes for the first time. In fact, what may shock you is that you’ll actually be trying and still fail”. This have proven to be true.

I’ve heard about a 1/5th of the class may have failed one particular exam we just had, I was fortunate to pass that one. We’ve had 4.5 courses, and here and there people are a good number of people struggling to adjust to what medical school requires. We’ve had at least two students leave, one on leave of absence to restart next year and one person just decided medical school wasn’t for them. However, I wasn’t so lucky on the second biochemistry exam however, I’ve passed the first exam, failed the second, a fail in that course is a B- mind you. Currently, I’m making some adjustments so I can hopefully defeat the last exam coming up in a couple of weeks. Interestingly, the hardest part of medical school is trying to zero in on how you should study, especially as a battery of professors teach the course and write the test, so it’s hard to figure out what style you should use. In general, we’re learning that the rule of thumb is to ‘simply’ know everything that’s ever uttered — unless the professor concretely states “This will not be tested”, and even still take that with a grain of salt. After the exams I had a good friend stop by from California, I took him on a three day tour of Boston including the public library. Every medical student needs time to unwind.

In our program, we round on patients during our first year. I signed up to work with outpatients, so I flip flop between urgent care and family medicine to learn what “normal” patients will present like. Later, I’ll switch over to inpatient hospital rounding to get used to what a “normal” inpatient is like. Clinic rounds are a great break from studying, and it’s a great chance to try to make links between course material and patients. It seems almost divine that things I learn in class end up presenting themselves rather frequently in clinic: during the “back and limbs” section of anatomy I saw patients with rotator cuff injuries, when we started the cancer lectures in biochemistry I had to work with a physician while he tried to discuss the patients prognosis (and unfortunately, neither prognosis was favorable). While discussing bad news with patients (cancer) I’ve learned they expect physicians to be understanding of their situation, but at the same time it’s important to be the “strong one” in the relationship, especially when they’re already scared. It’s odd to think that I just started a few months ago, and merely while merely dawning a ceremonial white coat and a stethoscope people, namely patients expect and admit so much to me. I’ve learned about people’s fears, ambitions, secrets, I’ve seen burly tattooed men cry because they’re in chronic pain, a pregnant mother who tried to commit suicide after her boyfriend ditched her after learning about the pregnancy. People really do tell their ‘doctors’ anything, it’s quite a position of trust. We were told that we’d encounter these scenarios during the first couple weeks of school, but we thought as infant medical students they were just trying to “scare us straight”, but they weren’t kidding.

You hear a lot of painful stories, physically and emotionally, but you maintain a calm and caring face while listening and maybe later you have time to reflect on how you really felt — scared, but that’s okay.

In a few hours I have clinic duty again, I will put on my white coat and engraved stethoscope and put a smile on my face to project confidence while I interview patients. I will get a history as usual, present it, and the results will be added to the electronic health record. After that, I’ll go to school and study for several hours, head to anatomy lab (we bisected the head yesterday) and study some more. I’ll return in the evening, perhaps after 9-10 PM, eat and study some more, then go to sleep to wake up and study again.

Study hard premeds, medical school is wicked hard, but it’s also an unforgettable experience.

My Interview with MedschoolHQ

Hi,

My exams are almost over, just one more to go — they were very hard in case you were curious. A few weeks ago, before the exams, I was invited to have a podcast conversation with Dr. Ryan Gray of Medical School HQ. So, after stripping off my tie from clinical site duty and me frantically trying to remember what my Skype screen name was we finally got down to it. It was sort of surreal, as before applying to medical school I book marked this site because I really enjoyed the content. If you haven’t heard of Medical School HQ, then it’s a good link to add to your favorites list. Here’s their about statement:

MedicalSchoolHQ.net takes the RELEVANT pre med and medical school topics and creates a one-stop shop for you to quickly get the information you need. Follow our current, constantly updating “Pre Med 101″ page for an easy step-by-step guide to your pre medical years. We´re working hard on developing a Medical School 101 for those students going through it right now. We are constantly looking for new ideas that will help YOU. Please let us know what you need to succeed and we will provide it.

MedicalSchoolHQ.net is the work of physicians. This site is here to help medical school applicants guide their way through the admissions process. It’s here to help medical students pick a specialty, aces the board exams and more. We remember how the MCAT and the AMCAS were (and still are) very intimidating and overwhelming for anybody wanting to apply to medical school. We remember how the USMLE seems to be the make or break test to get you into the residency of your choice. Let MedicalSchoolHQ.net be your hub of information to simplify the process.

My podcast interview was their 95th installment, I haven’t listened to it myself because I cringe at the thought of hearing myself speak (haha). But, if you’re interested in listening and learning some private details about my experience as a nontraditional medical school student please check out:

There’s a Storm Coming: Exam Week

Hi,

I’ve been a little pre-occupied with studying, human dissection and medstudent tom-foolery. Starting tomorrow, my school has an exam block for MS1s (first year medical students). At my program, we have a traditional schedule, that is classes from 8 AM until the afternoon: Biochemistry & Molecular biology (and you thought you’d never talk about pKas again), Gross Anatomy (lab and written exams), Human Behavior in Medicine, and Public Health/Law. I have three tests this week, every other day, and the last test next Monday. Interestingly, as time marches on I’ll have less exams to take until Thanksgiving (Turkey Day) — I look forward to this idea.

There’s a lot on our plate as first year, lots of studying, lots of cramming. Though, cramming takes on a different meaning compared to undergrad: in undergrad cramming meant you studied 48 hours before the exam, in medschool cramming means you’ve always been studying and it’s still not enough so you need to really work your buns off as the test approaches to stuff every last bit of information into your brain you can before the exam. I’ve heard from my upperclass mates that this pattern abates, dropping off over time as you become more comfortable with the material and testing style. But for now, most of us are stressing out over the exam block coming up, some more than others. At my school, there are a lot of industrious medstudents who’ve fulfilled a masters/extension to place into my medical school wherein they have a lighter load because they don’t have retake classes they’ve already aced. These people worked for it, and their reward is a little less testing around this time — bravo. So, if you’re one of the people who decided to go this direction, be confident that you aren’t wasting your time once admitted if you set yourself up with the right program. A lot of us however didn’t go this route, so we need to have a full block and we cry ourselves to sleep internally every night as we try to keep everything together, know the minute details while hopefully still understanding the big picture.

So, how do I feel? Pretty freaked out to tell you the truth. But at the same time I’m elated to see that medical school is every bit as challenging as people made it out to be, because it means that hopefully by the end I’ll be a better person and perhaps (if I’m fortunate) a tad smarter. We have a pass/fail system at my school with no internal ranking, this is to help cut down on competition amongst ourselves, but internally I’m sure a lot of us still want to do well just to prove it to ourselves that we ‘belong’. I’m lucky though, my classmates are ultra supportive and we study together randomly all the time — in fact, I randomly crash study groups all the time.

This past Friday, I decided to take a study break and I visited the person who interviewed me. You see, she told me to visit her if I decided to attend the program after my interview. I laughed when she told me that, and said of course because I halfway figured I’d be rejected and she just didn’t want to ruin my day. So, I lived up to my word and paid a visit. We talked for about an hour and a half, she told me why she wanted me to be admitted and I told her how I felt about the interview day and her interview. She later showed me her lab where she helps head the amyloidosis research, where both PhDs and MDs work together on a translational research project. We viewed a slide of amyloid protein stained with a Congo Red dye. You’ve probably heard of amyloid protein before, and the first thing to come to your mind is probably Alzheimer’s, but the protein plaques can also aggregate in your visceral fat around your gut and heart (in the septum). You can diagnosis someone with amyloidosis by taking a sample of fat from the visceral region, using it to confirm images of a hypertrophied septum thus confirming amyloidosis — the day actually turns apple green under polarized light, it’s still debated why this happens exactly. It was awesome because I just learned all of this a few weeks prior, and I have a test on the subject (and many others) tomorrow morning, so that’s one question I probably won’t get wrong.

Received First “Pass” in Medschool

I’ve been in medical school for just a few weeks, I thought I’d leave some highlights and help document my own memories:

Intubated dummy

Intubation is an emergency procedure usually done in the emergency room to secure the airway of someone who can’t breath on their own and you have some trepidation about them drowning in their own secretions. My medical school, more specifically emergency medicine interest group at my program, had an open opportunity to anyone who dared to try to intubate an anatomical dummy. A few weeks before I started medical school I got caught up in the show Boston Med, in that episode a fresh MD intern tried to intubate a patient and failed to do so — I know this is a skill you need down because time is the essence in both saving the figurative patient and reducing co-morbidites. So, what better than to get an idea of how hard this procedure is then by trying it as a first year with absolutely no training except the crash course 30 second mini lecture I received beforehand. The procedure is straightforward, but not without it’s caveats:

1. Place laryngoscope into oral cavity, hooking the tool towards the basement of the tongue. Ultimately, the purpose is to reflect the tongue out of the way.

2. Push and lift the laryngoscope, being sure not to roll the tool backwards as this will either break the patients teeth (best case scenario) or crack the maxilla (bad news). The point of this movement is to expose the trachea (the vocal chords end up being a dead give away, no pun intended).

3. Once you’ve located the trachea, you stick a tube with a balloon attached down their trachea, you must be sure to not insert the tube down the esophagus (ultra bad news). Within the tube there’s a stiff, but pliable, rod that will keep the tube from collapsing as you’re trying to gently/aggressively shove the tube down the trachea. Once you’ve done that, you put about 10 cc of air into the tube to both keep the tube in place and prevent fluids from the patient from regurgitating up and going into the lungs (also bad news).

4. Then while holding onto the tube, you pull out the rod, and place either an attachment to bag to manually ventilate for the patient or the ventilation machine.

It’s pretty straightforward, though performing it is another story. I failed the first time, I wasn’t aggressive enough to expose/open the trachea. I then took a mental break and tried it again, this time I got it but after a brief struggle. Finally, after gathering my experience and thoughts I tried again and this time I intubated right away! I’ll definitely will be practicing this more in my 3rd year in the clinical skills laboratory. I never really thought of myself as a hands on person, despite constantly working with my hands, but I liked it and I’m excited for my future emergency room rotation on the wards as a 3rd year.

Signed up to shadow trauma surgeon

You never really know what you’ll do by the time you finish medical school, at least that’s what I’ve been told repeatedly. I suppose this hit home the most when, during my interview, one physician spoke to us about her own experience in medical school until now. At first, she couldn’t see herself doing anything but primary care, now she’s a trauma surgeon. She said to us during our interview, “If you come to this school be sure to contact me if we’re interested in shadowing in trauma”. So, I did followed through and contacted her, I have my first shift sometime next week. Let’s see who that goes, my primary goal is to not get in the way.

Gross Anatomy

The naming of gross anatomy proves that science people do have a sense of humor. Interestingly, it’s not so much the person or the physical anatomy that grosses medical students out. Instead, it’s that we’re inclined to like people and I won’t lie, a lot of us are quite sensitive emotionally (at least it’s that way in our class). The person who donates their body is the most beautiful and inspiring person you’ll never meet (unfortunately, postmoterm). For medical students this is a rite of passage, we all deal with the emotional and psychological impact in our own way. For me, it was with a pint of ice cream — though, I didn’t finish the ice cream yet as I was too tired to physically raise the spoon to my face. Last week we prepped the donor (and ourselves), this week we started dissection on her. Like most medical schools I’d imagine, we started with the back as they have huge muscle groups and there’s a lot of room for error due to the nature of the back, they have you start with the back first so you can learn how to work a scalpel. This is a huge effort, and requires a lot of team work. There are 8 members in my team, but only 4 of us are there for a session — but we are one unit. One team starts, then another team comes and finishes. In between, there’s something called “transition of care”, this is analogous (and purposely so) to patient hand offs in the hospital. Each day there is a team leader (from the 4 person cell) who’s responsible for making sure the next team leader (of the other 4 person cell) knows what’s going on and what issues have come up. If we don’t finish our objectives, it’s the whole teams responsibility to self schedule a team to finish the work before the next dissection assignments. Today, I was part of the first team and all of my awesome team members worked together and achieved our goal today.

We Start Seeing Patients this Week

A lot of medical schools try to get their medical students into clinical thinking as soon as possible, typically with mock patient interviews from skilled patient actors. Our 3rd week into medical school we’re already schedule to start doing rounds with either residents are MS4 medical students and seeing real patients. Our responsibility is to take their medical and social history (probably from the nth time), and present out information to our superiors. I’ve already received my white coat, but it’s not in my possession because I gave it back to the school to get it embroidered as required. I’ll get it back this week before I start seeing patients. Around the same time I’ll be receiving my stethoscope and otolarynscope, both of which I probably won’t realistically know how or need to use for some time. For now, my focus will be on seeing patients, and learning how to build a report while gaining skills at getting an accurate and informative history from patient interviews. I’m a little nervous about missing information more than anything.

Survived My First Medical School Exam

The school crunched what would be a semester in undergraduate of Histology into 5 days (literally) followed by an exam. As I’ve never formally taking Histology I was a little apprehensive about this, as were many of my classmates, many of whom have never had experience in the subject matter either — though, it should be noted that some of my classmates were savvy enough to have taken a masters post bacc course (or post bacc with no degree) Histology course for 7 weeks prior to this. I mention this because if you’re of those people who’re doing post bacc work you should know you’re work isn’t going to waste, those people were comfortable with the cram session. For the rest of us, it was a gratifying torture, but we got through it. My school is a pass/fail school, though we can personally see our own scores so we can know how we’re doing. I passed with a comfortable margin, in fact the class average was rather high considering the circumstances. I should mention that the biggest difference between medical school and undergraduate work is that you really need to work with others to make things work, there’s just too much for you to think you can cover by yourself in too short of a period of time. I go through this period by planning studying groups, crashing study groups, and showing up to office hours. Without my class I’m not sure if I’d be sitting so comfortably right now as I write this blog, instead I’d likely be panicking and wondering if I’ll make it — turns out the signs are positive.

Interview Tips for Medschool Applicants

Hello All,

Just finishing up the second week of medical school, it’s been a really busy week. I have a test coming up on Monday, we’re covering a semester (or quarter) of histology within a week — though, we’ll revisit it again in more depth next year. We”re the first year they’ve tried experimenting with this “crash course” in medical histology so that everything, coincidentally we’ll also be the last as they’re switching to system based curriculum for entering students next year. Though, it should be noted that our second year is clearly system and diagnostics based. Regardless, a medical school will make you a doctor, but it’s our job to try to get the best out of the experience to later to good physicians. Some of you have been given a chance to attend a medical school interview, if so congratulations! If not, there’s still plenty of time to receive an interview, some people in my class were invited rather late and accepted almost the week before school so keep pushing through. And remember, if you don’t get in then improve your application and re-apply.

So, with that aside, here are some interview tips (this list got longer than I expected, sorry not much time to edit it down!):

Preparation

1. Do a ridiculous amount of homework for your interview: check the local news online, check their website for their local interest groups and try to see how you’d fit into their program and mission.

2. Know your application better than anyone on Earth. Nothing is worse than coming off as a fraud, and the easiest way to do that is to appear like you fluffed your application. Know your application, know why you participated in X groups, why you took a gap year, understand your influences and weak points. They can only go off what ever you’ve presented them with, don’t let them know you better than you know yourself as it won’t go well.

3. Practice coming up with main themes for you answers for the interview. You can try doing a few mock ones if you wish, I’m lazy and shy about those types of things so I just came up with main themes and practiced by myself (lack practicing for a speech). Though, to be fair, I’ve given a lot of speeches and talks so it’d probably be better to just try with others. There are plenty of books with “sample” interview questions, just pick one up and go through it to come up with your own answers. Also, just search Youtube for interview tips, some of it is baloney but it’ll get your gears turning.

Logistics and Transportation

4. Purchase airplane tickets at least 6 weeks prior to the interview, after that they rates really will jack up. Note that the rates change throughout the day, so check multiple times (or set alerts for price deals etc). You probably won’t rack up enough miles to make use of any frequent flyer program, they tend to do a good job of keeping you away from cashing in, so don’t get too picky about riding on a certain airline.

5. Rental cars are pretty pricey to hang onto during an interview, but they offer a lot of flexibility. If I were interviewing again, I would have rented a car less and probably have just used Uber (with a back up plan of using a cab). Though, depending on how far out you stay from the school while visiting a rental car may be the most logical way to go.

6. Show up and find the place you’re supposed to arrive at about 45 minutes to a hour early. It’s okay to ask the staff if you’re in the right place, after you’ve confirmed just hang out and have a seat and try not to bother the staff. Be extra friendly, the staff and faculty at medical schools are infinitely closer than your undergraduate experience so treat everyone you meet (even the janitor) as if they’re potentially the dean of admissions. If you’re early and nice to everyone it’ll help cut down on the nervousness, at least it did for me.

Fashion

7. If you’re a male, learn how to tie your tie. There’s no shame if you don’t, but if all you have to depend on is your pre-tied tie done by your uncle three years ago then you’re setting yourself up for stress during you interviews. It’s not hard if you practice it a few times in the mirror — you can find plenty of videos on Youtube. Also, don’t dare go to your interview without going to a tailor to get your pants and suit cuffs hemmed to fit you. This is the secret to looking professional: you can start off with a relatively cheap $100 suit and pay another 20-30 for tailoring and the result will make it look like a $1000 suit. You don’t want to go looking like you’re wearing your dad’s suit. You don’t need to go get a customer tailored suit, just go to a cheap place that’s been around for a while and ask them for suggestions about fit. Ideally, when you sit your paints should reveal your socks by a few inches and not drape over your shoes when you walk or sit. The cuffs of your white collared shirt should show just barely by perhaps half a centimeter when you’re wearing your suit-jacket, furthermore the jacket should be long enough to stop at your wrist but not after your wrist widens to your hands. However, the caveat here is that if you don’t at least try to start with a suit that fits you in the chest and back especially, then you’ll likely spend another few hundred dollars to get those sections tailored as it takes a lot of work and a skilled hand. If you’re fashionably inept then consider bringing a “professionally dressed” fashioned coordinated friend with you. If you have a thin frame, I’d suggest going with an Italian cut (slim fitting) in the standard medical school charcoal — it’s significantly cheaper to tailor a suit that almost fits you, hemming is usually the cheapest and most bang for you buck thing you can do. And of course, don’t neglect on your shoes, but don’t splurge either however don’t come into the place with squeaky clogs either. You whole goal should be to look like a respectable doctor, after all you will be one soon right?

For females, you don’t need to dress like a puritan or anything, just dress professionally equivalent to your male counter parts. I’d suggest not wearing shoes that “click clack” too much, as they’re both distracting for you and everyone else during the long interview day. Be sure to wear shoes that won’t bloody your ankles (or make adequate preparations in the heel for padding if you have choice). I won’t suggest much more about how to dress, especially as I never saw one female incorrectly dressed for the interview (guys on the other hand, that was a crap-shot). Just be sure that you can be confident in whatever you wear.

There are a lot of people in my class with tattoos (arms, back, etc.), while it’s okay to have them it’s also considerate to cover them for your interview. After you’re in, sure rock that tattoo of Satin devouring kittens, but at the beginning just try to be respectful of others’ beliefs. I personally think tattoos are awesome, but as a first impression don’t make it into a philosophical battle of the merit of tattoos and bias.

The Interview

8. Be yourself (hopefully that has positive implications) — it’s much too tiring to be something else in my opinion. This translates to standing up for yourself and your opinions during interviews. If you have an opinion, and a rational manner of defending it then by all means it’s okay to disagree with an interviewer. However, you don’t need to pick fights or win battles, just be okay with being fine with “agree to disagree”. If they convince you, fine, but don’t just be a yes “wo(man)”.

9. It’s okay to ask the interviewer questions about the program, about their position etc. You’ll have to “imagine” that you’ll get into multiple programs and you’re just trying to evaluate the best one, this will keep you objective (but, don’t be arrogant about it). There’s a fine but discernible line between arrogance and confidence. In fact, ending the interview with no questions is a passive way to tell people you’re that interested, but don’t ask questions you could have/should have easily found out if you just did a little research. The better your questions, the more they’ll know you care and have given their program careful consideration.

10. Write down the interviewers’ names, this will make it easier for you to write them correspondence later if you choose to do so.

Post Interview

11. Jot down things you liked and disliked about the program immediately while it’s fresh. This way, if you do write a letter to the school (letter of intent, I didn’t write any so I can’t help you there) to let them know your intent of matriculating if accepted you can write legit things as opposed to blowing smoke up their butts’. If you receive multiple acceptances having this list is incredible when it comes to weighing the pros and cons of the program. I kept notes throughout the day, but I wrote them in another language so no one else could peak at what I wrote; if you don’t have that advantage then just write sloppy short hand that only you can read. These notes can in handy actually even during the interview when I was able to address brand new things I found out during the tour about their patient population etc.

12. Don’t, don’t, don’t, don’t become complacent because you’ve landed a few interviews. Until you’ve landed your acceptance it’s best to treat every interview like it’s the most important interview in the world, heck if afterwards you should be serious about them. If you’ve already gained an acceptance, unless your dead set on going to that program, consider continuing to a few more interviews as you might learn something new about other programs. It’s also decent experience for what you’ll need to do next for residency interviews (though, those are probably a lot more fun).

13. Be humble. Congratulations, you’ve interviewed and whether you get it or not, it’s a monumental step. But, there are those who aren’t accepted for one reason or another, be sure to remember that not too long ago you were just as nervous and unsure as them.

Remember, if you’re invited to an interview then the probably already are at least interested in you (and may even sort of like you). All you need to do is either win a few people over who may not be sure about you and/or prove that you’re not a phony and all the stuff you said on your applications are congruent with who you actually are.

Good Luck!!!!