pre med

Letters of Recommendation: How Do I Get Em’

Contact me on twitter: https://twitter.com/masterofsleep

Welcome back,

Applying for medical school is an odd process, especially if you’re a nontraditional applicant. For myself, I rushed to complete the premed requirements and my major/minor/undergrad research. After being molested by academia, you’re thrown into the hardest entrance exam in on the planet (no hyperbole) for 5-6 hours. Then you are asked to complete several other Herculean feats to complete your medical school application, abbreviated as the AMCAS:

- Primary Application

- Scores: MCAT, and GPAs (two separate undergraduate GPAs will be calculated by AMCAS), a masters degree will not shroud undergraduate GPAs, it will however show improvement.

- Personal statement: bust out your feather quill to write the best personal statement you’ve ever written — no, the one you wrote before won’t do either.

- Work Activity Section: I’ve already covered this in another article.

- Letters of Recommendation: this article will focus on obtaining a letter.

So, I’m often asked about the subject of “Letters of Recommendation” (LOR, or LORs when plural), I’ll tell you how I handled them in this article and attempt to answer the following three FAQs:

- From who do I get them from, and how important are LORs?

- How do you I ask letters for a recommendation?

- When do you need to start thinking about letters of recommendation and what is the timeline?

- From who do I get them from, and how important are LORs?

Most medical schools accept two types of letters individual letters and/or committee letters. If you are traditional premed then go with whatever your premed adviser suggests as the standard protocol for other premeds from your university who have been accepted. From what people tell me, that usually entails obtaining a committee letter if you’re a traditional premed. However, as a nontraditional I had no idea if my university actually has a premed committee, nor did I care to receive premed advising as a late entry nontraditional. Thus I obtained individual letters from various professors — so this article will focus primarily on individual letters. In my own case, having individual letters seemed to work out because I was offered four acceptances by mid winter. There are probably pros and cons to either form, for example committee letters are probably logistically a lot easier to obtain and they probably know what to write to make you look like a good applicant. The downside (just to play devil’s advocate) is that you’re really hedging all of your bets on the committee who probably don’t know you very well personally besides the occasional meeting. The upside of the individual letters is that if you chose you writer wisely you’ll end up with a very exceptional personalized letter. But you could also chose the worst person to write a letter for you, and on top of that you’d have to handle all the logistics of making sure your letters go to AMCAS on time on a case per case basis. Before committing to schools be sure to check with each school’s policy because sometimes they do have very specific requirements.

In my case, my individual letters were:

- Human Physiology Professor and my research principal investigator

- Chemical Engineering Professor and the chair of my research scholars program

- Chemistry Professor and research adviser for research scholars program

- Political Science Professor who I volunteered with for prison education programs

- The dean of my major

I chose writers who could vouch for what I felt were my strengths like work ethic and science background (letters 1, 2,3,4), my commitment at bettering my community (letter 4), and someone who could vouch for my patient experience (letter 5). If you have individual letters coming in, use them to compliment your AMCAS. My principal investigator worked together quite intimately, so they also had no problem ameliorating my perceived shortcomings for the admissions committee. I had all but one of them upload the letter electronically after I gave them a written tutorial about how to upload it to be sure it arrived on time.

Either way you choose, individual or committee letter(s), there’s no way you can guarantee the admissions committee will see the writer’s arguments for your admission as satisfying or cogent. It’s hard to quantify how important LORs are, because we have to consider a lot of variables such as the rest of your application and letter quality, but I’ll just say in my case my letters came up favorably during all of during my interviews (unless they were not given access to the LOR prior to the interview). So, I think it’s probably safe to assume they’re important and shouldn’t be thrown together haphazardly, the quality and amount of effort you put into obtaining good LORs will correlate to better LORs.

- How do you I ask letters for a recommendation?

You may be in school or out of school, either way the strategy isn’t that different. Now, I work with professors everyday for work, and I see how busy they are and how to get through to them. Check online, go to their office hours. Bring transcripts with overall GPA, classes you want them to see highlighted, plus any other recent accolades. Tell them why you want a letter from them specifically, when you intend to apply, and when you’ll need the letter by. If they agree give them at least 6 weeks (make the window too short and they’ll refuse, too long and you’ll never get a letter finished). Even if you obtain a verbal confirmation that they’ll write you a letter, be sure to follow up with a formal request for both your records by email, it’ll help keep the record straight for both of you. Remember, your letter writer probably doesn’t have time to write you letter, but they’ve kindly agreed to postpone their other responsibilities for you.[[ (quick reference): [insert Corran letter] I asked for all of my letters in person.]]

If possible make in person verbal requests, bring nothing with you but a succinct explanation of why you want a letter from them, and verbally confirm they can write you a “strong” letter of recommendation. If they agree to write you a strong letter then tell them you’ll follow up with a written email with your transcripts/stats, and means by which they can submit the letter. Some professors will tell you directly, “I don’t think I can write you a strong letter”. It doesn’t necessarily mean they curse your existence, they’re probably being honest because it translates to “I don’t know you enough to write you a strong letter”. On the other hand, in the unlikely event that they actually despise the day you were born and have a picture of you on their dart board, you wouldn’t want one from them anyways right? Don’t take it personally if they refuse, they’re likely doing you a favor by saying “no” either way. If they say they can not write you a strong letter of recommendation thank them and move on.

Follow up with a very easy to read email. Now, I assume your writer will be an excellent reader, but they don’t have time to read through a gregarious lengthy email. Furthermore, they’re putting their “street cred” at risk as a professional by attaching their name to yours, so it’s quite an honor to receive a strong letter of recommendation, make sure you’re doing your part to make it easier on your letter writer. So keep it short and sweet and unambiguous, so be sure to include in the formal written request:

- Let them know the exact name you used to registered for AMCAS as well as your AAMC ID#. Remind them the letter requires an official letterhead.

- First and foremost, thank them for agreeing to write you a strong letter by a specified date — letters will likely roll in late if you rush the writer without prepping them properly or allow the responsibility to fall onto them to ensure timely completion.

- Give a very brief narrative about you and your intentions (a short paragraph).

- Stats: give them a summary of your GPA/CV, favorable or not. For their peace of mind include a PDF attachment of your transcripts/CV, let them know it’s attached and the correct title if you have multiple attachments. Highlight the pros of your stats, offer to talk more in depth in person about personal circumstances that may of left bruises on your transcripts.

- Concretely tell your writer what types of things you’d like them to address.*

- Give them a concrete way to submit the application. This will mean giving them the physical address of the AMCAS letters service if they want to go snail-mail, or providing them the links and steps to upload your letters online. If your letter writer finishes the letter and can not send it because of poor instructions it’s not the fault of the writer.

Don’t be surprised or insulted if the professor who agrees to write you a strong letter first requests for you to draft a letter of recommendation for yourself then submit it to them to modify as template (it’s very common in the research world). Above all else you should always know your strengths and weaknesses of your application. Use this knowledge form a draft that shows your good points and rationalizes the humps on your application without making excuses. There’s a good chance that the LOR they actually send will appear nothing like your draft, but the highlights you wanted will likely still be captured.

- When do you need to start thinking about letters of recommendation and what is the timeline?

You should start thinking about who would make a good candidate for strong letters as soon as possible. The sooner you understand the strengths and weaknesses of your application the sooner you can start pulling together your writers. If you’re afraid of writers forgetting about you later, let them know about how you’d like a letter later, and send them an email as a record to confirm the confirmation. When it comes time to ask them later, you could pull that record up to help refresh their memory.

Give your writers ample time to compose a good letter for you, if you try to drop a bombshell on them at the last second don’t be surprised if you get a mediocre letter or if they outright refuse out of principle alone. You can turn in your primary AMCAS application prior to receiving any letters, however schools will not invite you post secondary application unless you’ve submitted your LORs they request for their program. So, it’s important to consider the timeline when you’re requested strong LORs. I approached my writers formally in April (primary applications open in June) and I gave them a deadline of the 3rd week of May. This gave my writers enough time to compose the letters, and enough time for me to discretely nudge my writers when they were falling behind.

In closing…

The amount of preparation and methodology you chose to use to obtain your LORs will have a correlation to the LOR quality submitted. If you put in the minimal amount of effort then expect a minimal LOR. Also remember, your writer (especially professors) are putting their reputation on the line, so be courteous and respectful. Be sure to thank your writers after the process, and keep them up to date on your progress or lack-thereof (as a tutor I really loved when students got back to me about grades or when I wrote a rare LOR for them). Be honest, respectful and appreciative while constructing your professional network with your writers.

Have something to add about your experience with committee letters or individual? If so, feel free to share.

Thanks for reading, and feel free to contact me anytime https://twitter.com/masterofsleep

*updated on 12/18/13 Added something about the letterhead. Thanks SDN user.

Organic Chemistry: Competing Reactions, Part 4 Quick Guide

Alright, so we are finally to the last installment of the Sn1,Sn2, E1, E2 guide bonanza. From here on in I will refer to the substitutions and eliminations as fundamental reactions collectively. I really wanted to get this entry out before people had finals, hopefully it worked out for you as well. So, let’s get the last entry about fundamental reactions out of the way.

Competing reactions

Eventually the average student will be able to discriminate between the basics of the fundamental reactions. The harder part of the course usually involves being able to discriminate with a fair degree of certainty when a reaction will undergo a Sn1, Sn2, E1 or E2 process. At times the reaction may favor only one mechanism, or it may favor all of them– competing reactions are often why you’ll spend those extra hours in Organic lab purifying the product. Sometimes the reaction is impossible, therefore the answer to the question stem may be the dreaded ‘no reaction’. Interestingly, it takes a remarkable amount of courage and confidence to write ‘no reaction’ on an exam.

Organic Chemistry will be the first course where you are truly inundated with details, i.e. the first time you had to try to drink from a fire hydrant so they say. They key is to work a lot of problems, and keep the details straight. Working a lot of problems will make you familiar with they manner that I will demonstrate to make competing reactions less troublesome.

First, let’s take all the information we already know about fundamental reactions and place it into a form that’s easy on the eyes:

|

|

Reactions |

|||

| Substrate |

Sn1 |

Sn2 | E1 | E2 |

| Me-X |

X |

|||

| 1 |

X |

X |

||

|

2 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

3 |

X |

X |

X |

|

Table 1

Some will say Sn1 can also reaction with a primary alkyl halide, but in practice this would quite a monumental feat because primary carbocations are extremely unstable under normal conditions. So, I left it out to avoid confusion.

The table listed above is just an amalgamation of the previous tables I’ve listed so far in the previous guides. From this chart we can state several axioms:

- Me-X alkyl halides are restricted to Sn2 only.

- Primary alkyl halides can undergo all fundamental reactions except E1 and Sn1.

- Secondary alkyl halides can undergo all fundamental reactions.

- Tertiary alkyl halides can undergo all the fundamental reactions except Sn2

In other words, if you get a problem and it’s a Me-X, it’s a slam-dunk, it has to be an Sn2 or NR if the proper reagents aren’t there. Whereas, secondary alkyl halides a multitude of products can be formed all depending on the conditions. So, let’s pretend you had a pesky secondary alkyl halide, such as 2-chloro-3-methylbutane. If we glance at table 1 we are quickly reminded that it can undergo all of the fundamental reactions, given the right conditions.

Selecting by Reagents:

If we put 2-chloro-3-methylbutane with a strong nucleophile we should unequivocally expect an Sn2 and/or E2 reaction. If we put 2-chloro-3-methylbutane with a nucleophile with a solvent (or other conditions) favoring favoring the formation of the carbocation intermediate we should expect to see only Sn1 and/or E1. To summarize what I just said:

| Similar Conditions:-Weak Nu: or base-Polarizing solvent- Rate liming step: carbocation intermediate formation | Similar Conditions:-Strong Nu: or base-Any solvent works, but aprotic solvents best-Rate limiting step: transition state formation | |||

|

Uni-molecular |

Bi-molecular |

|||

| Substrates |

Sn1 |

E1 |

Sn2 |

E2 |

| Me-X |

X |

|||

| 1 |

X |

X |

||

| 2 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| 3 |

X |

X |

X |

|

table 2, Nu: = nucleophile

Now, if we go back to our 2-chloro-3-methylbutane, we’ve already figured out that if given the same conditions we can assert that the reactions will compete: Sn1 versus E1 or Sn2 versus E2. That is, given the same conditions you should expect either a unimolecular reaction competition (E1 versus Sn1) or a bimolecular competition (E2 versus Sn2).

Sn1 versus E1 Discriminating with Conditions/Reagents:

| Similar Conditions:-Weak Nu: or base-polarizing solvent- Rate liming step: carbocation intermediate formation | ||

|

Uni-molecular |

||

| Substrates |

Sn1 |

E1 |

| Me-X | ||

| 1 | ||

| 2 |

X |

X |

| 3 |

X |

X |

For all intents and purposes, for the first year of Organic Chemistry, it’s best in my opinion to just keep this as a rule of thumb:

When it’s a uni-molecular reactions (Sn1 and E1) expect a mixture products of both Sn1 (watch for rearrangements, and racemic mixtures) and E1.

In practice, selectivity between Sn1 and E1 is poor, as a result lots of products may form, with the most thermodynamic-ally stable product(s) being more abundant. In lab expect to use a lot of fancy lab techniques to isolate the actual product.

Adding heat to the reactants creates a carbocation either way, making the reaction susceptible to both Sn1 and E1. However, as heat is continually put into the reaction the alcohol (substitution) product will tend to dehydrate into the elimination product(s) (alcohols -> alkenes), for this reason in general higher and prolonged temperature biases towards elimination products. Therefore if you started off with 2-chloro-3-methylbutane, reacted it with water and heat, you’d form a mixture of alcohols and alkenes. But, if you left the lab and let the solution boil too long uncontrollably you’d come back only have mostly mostly alkenes. Cold temperatures would shut down both pathways.

Sn2 versus E2: Discrimination with Conditions/Reagents

| Similar Conditions:-Strong Nu: or base-any solvent works, but aprotic solvents best-Rate limiting step: transition state formation | ||

|

Bi-molecular |

||

| Substrates |

Sn2 |

E2 |

| Me-X |

X |

|

| 1 |

X |

X |

| 2 |

X |

X |

| 3 |

X |

|

When it’s a bi-molecular reaction (Sn2 and E2) expect a mixture of products for secondary and primary alkyl halides. However, know that E2 and Sn2 do not work with Me-X and tertiary alkyl halides respectively.

Discriminating between Sn2 and E2 is typically more clear-cut, therefore it’s an extremely testable point. If Sn2 and E2 are competing cold favors Sn2 and heat favors eliminations. You can select for E2 products by using a poor nucleophile but moderate/strong base.

Last Thoughts

If you are just starting Organic Chemistry it’s probably hard to imagine how these four reactions could possibly be important. However, as you gain more experience in synthesizing compounds you’ll soon find the trend to be more obvious. You’ll start the course by looking at alkanes, then perhaps looking at free radical reactions with halogens to create alkyl halides. Pretty much once you’ve loaded your alkane with a halide the sky’s the limit of what you can form given the proper reagents and lab equipment (with proper usage).

Remember, Biochemistry is just Organic chemistry with fancy nomenclature, the better you know Organic the more intuitive everything ‘chemistry’ will seem to be — though in Biochemistry you’re more interested in the results of the reaction than the physics of the mechanism itself.

As always, you can always find me on twitter: https://twitter.com/masterofsleep

Alright folks, back to writing tips about how to apply to medical school Good luck all you cool people with finals! I heart goes out to you as a former premed.

Organic Chemistry: E1 and E2 Quick Guide, Part Three

Welcome to part three, of the well…okay four. I originally intended to make this summary three parts, but in the end it looks like it’s going to be four. However, this entry will pretty much perform what I had intended, that is to wrap up the Sn1/Sn2 & E1/E2 reactions. I needed another entry to cover the infamous competing reactions. However, I didn’t want to hold things up for people with looming tests. So, here’s the plan:

- Wrap up substitutions, and finish with mechanisms of eliminations (E1 & E2)

- Fourth article will cover competing reactions

- If you have any questions, or things you’d like to see in fourth entry just message me here on at twitter https://twitter.com/masterofsleep

We have spent all of our time looking at 2-chloro-3-methylbutane. So far, we’ve seen that this secondary alkyl halide undergoes Sn1 reactions quite willingly, and less enthusiastically Sn2. There’s one more thing we can do with our secondary alkyl halide, and it’s called an elimination. There are two ways to form an elimination product, those are E1 & E2.

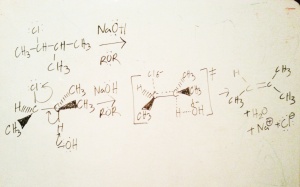

Although there are two new reactions to think about, because the Sn1 mechanism pathway is related to E1, and the Sn2 mechanism pathway is related to E2, if you’ve mastered Sn1/Sn2 then these next two aren’t that bad — I will refer back often to the mechanism of Sn1 and Sn2 as a foundation. Therefore when we use NaOH and 2-chloro-3-methylbutane, we should expect not only the formation of the nucleophilic substitution product i.e. 3-methylbutan-3-ol, but we should also expect the formation elimination products.

It is interesting to note that we could use the very same reagent NaOH, with the same reactant 2-chloro-3-methylbutane , and still form two disparate products i.e. a substitution & elimination product. This is also why you need to work hard in lab to purify your sample usually — fortunately Organic Chemistry labs usually don’t grade you on percent yield. The reason why this happen is because the hydroxide ion in our reaction can act as a nucleophile or a base, in this case a Bronsted base (you’ll never escape acid-base chemistry).

So, referring back to 2-chloro-3-methylbutane let’s see what happens when the elimination product forms….

Now, our first decision to make is, what mechanism does it follow? E1 or E2? If you’ve read the last two blog entries you probably saw that I went line for line on a chart of reaction properties to justify my answer. I could do that here, to justify how I would select for an E1 and E2 reaction. But, I want to do this in a more fluid and quicker method, relying on some basic Organic Chemistry ideas. As I already mentioned earlier, Sn2 shares similar mechanism traits with E2, and the same goes for Sn1 and E1. So, I just need to ask myself, does this problem look more like an Sn1 or Sn2 type of problem? Begrudgingly, I remember that this secondary alkyl halide can undergo both Sn1 & Sn2, so that means that this problem can actually undergo both E1 & E2. But, in this specific problem, the reagents favor Sn2 (NaOH is a strong base, and the solvent is an ether) so they should also favor E2. Therefore, the problem above is an E2 reaction.

Let’s not forget the minor product, this time I won’t show the mechanism:

Elimination Bimolecular (E2)

As a rule of thumb, when you see a reactant, and a double bond (or any pi bond) suddenly appears on your product then it was likely an elimination. There are three things to carefully annotate in the mechanism of E2:

The confirmational isomer of our reactant should be in anti-coplanar orientation. The easiest way to pull this off is to orientate the hydrogen that’s going to be plucked off by the base (the acidic hydrogen) and the leaving group into the planes I left them in using the 3D orientation drawing I used in the mechanism.

Besides the usual arrow pushing mechanism routine be sure to clearly label the transition state demonstrating:

- Three partial bonds, 2 sigma bonds and 1 pi bond (see E2 mechanism drawing)

- Two delta negatives, one on the leaving group and another on the base. If you don’t there’s a good chance you’ll only receive partial credit. (see E2 mechanism drawing)

- The rate limiting step of the reaction is the formation of the transition state. (see E2 mechanism drawing)

Later in Organic Chemistry you likely won’t be asked to show the mechanism of E2, but at some point you will be tested directly on it.

Elimination Molecular (E1)

For our next reaction we shall use our good friend 2-chloro-3-methylbutane as a reactant, and leave it boiling water for same time. You should already know that these conditions favor substitutions along the pathway of Sn1. If this doesn’t make sense, look back at the Sn1 versus Sn2 Chart. Now, being that we know that these conditions favor Sn1 we can extrapolate that this reaction can also proceed only the pathway of E1.

If you are already familiar with Sn1, then E1 shouldn’t be a big change. Like Sn1, the rate limiting step of the reaction is the formation of the carbocation intermediate. It also should be noted that carbocation intermediates when formed can be isolated, whereas transition states never can be isolated in practice — for this reason a transition state should never be reformed to as an intermediate. There are several things you should be sure to capture in the mechanism:

- Identify the ionization step of the substrate

- Label the intermediate carbocation, watch for hydrid shifts etc.

- Double check to make sure you’ve accounted for all of the products

As you can see from our answer in E1, we end up with multiple products, just like E2. In my example we ended up with the same result whether using E1 or E2, this won’t always be the case. For example, we could of started with a trickier example reactant, and done a number of hydrid shifts, this would of given us a product likely only obtainable via E1.

Product Stability

Within the world of eliminations the most thermodynamic stable product is the major elimination product, fancy talk for pick the product that is the most substituted. Then be able to use factors such as Zaitev’s Rule to discriminate further if there’s a close call. Predicting product stability tends to be a pretty big testing point, so you should feel comfortable ranking the products of E1/E2 reactions [collectively called alkenes] in order of stability.

That’s pretty much it for E1 and E2, they actually aren’t that bad if you already have a solid hold onto Sn1 and Sn2 because they’re closely related. The only difference really is that the reagent acts as a nucleophile, attacking a electron deficient center on our substrate and under going a substitution for a leaving group. In eliminations our reagents act as bases, abstracting a slightly acidic protein away from our substrate, and the loss of our leaving group, ultimately this results in the formation of a double bond.

That’s pretty much it. Now, there’s nothing left to do but practice. If you felt sort of lost about the whole explanation I’d encourage you to go read over Sn1 and Sn2 again, or perhaps rework some problems etc. If you are having problems with the whole guide as a whole then my best suggestion for you is to go review acid base chemistry in the Organic Chemistry text. This may sound like a strange suggestion, but this is because at it’s heart most of Organic Chemistry is just about an electron-deficient area motivating an electron-rich area to share the wealth, i.e. acid base chemistry.

The next, and last entry will cover competing reactions. A lot of people start to get frustrated around competing reactions, but it’s not that bad if you the logic of the reactions straight.

So, here’s a table summary of everything we’ve covered so far with eliminations in a fancy compiled table:

|

Things to Consider |

E1 |

E2 |

| Substrate | 3 >2 | 3> 2>1 (notice that methyl-X is impossible) |

| Kinetics | 1st order kR[substrate]; kinetics depends on only the concentration of the substrate | 2nd order kR[substrate][nucleophile], i.e. the kinetics depend on both the concentrations of the substrate and |

| Base (not nucleophile!) | Weak bases are a-ok | Strong bases only – bring a strong base or else loom in lab forever |

| Leaving Group | Good Leaving Group Needed | |

| Solvents | Solvents should encourage ionization | A lot of solvents work*, not too picky |

| Stereochemistry | No special orientation needed to start | Must be in coplanar transition state to proceed. |

| Rate Limiting Step | Formation of carbocation, this also means hydrid shifts are possible so expect rearrangements! | Formation of the coplanar transition state |

Well folks, that’s it for today. Good luck in your premed/MCAT days ahead of you. It’s all worth it, seriously.

Will be back soon with the last installment on competing reactions, then switching gears back to AMCAS entries.

As always, just follower or say what’s up on twitter, I love hearing from you guys: https://twitter.com/masterofsleep

Applying to Medical School: How I Was Left With $3

The real cost of applying is something to plan for when applying for medical school.

Two weeks ago I returned home from another round of interviews, in fact it was a multi-flight interview expedition starting from California to Boston, to Michigan and Chicago and back. I had an interview just about every other day for a week, so it allowed some time for me to both enjoy a post interview celebration beer and figure out how to get to my next destination. All and all, I’d say the interviews were moderately successful all of the programs were sending good vibes, though admittedly the Chicago interview was a little tough because I was surprised by the format — my interview was first thing in the morning, usually schools feed you and do some icebreakers before running you through the meat grinder. The cheapest way to travel to these three cities, and return home was to take seven flights in a week; I dare say I’m a airport screening professional now.

Again, you may be wondering why would anyone throw so many interviews together, well it’s pretty simple: pure finances. The process of playing to medical school is rather expensive, as applicants should pay for the MCAT prep materials (cost varies by person), MCAT test registration (hopefully only once), primary applications, secondary applications, flights, hotels/motels, rental cars, bus/taxi/train fare, food, missed time from work, it’s a large investment. An applicant can easily spend 2-7 K all depending on their individual situation. Of course there are those who pay significantly less: Fee Assistance Program receipts, and the brave souls who sign up for early decision may end up paying significantly less if all works out. But there are also those who pay significantly more: additional MCAT prep (~1-2K), MCAT tutors (40-100/Hr), admissions advisory companies (sky’s the limit) etc. My fees fell somewhere in the middle as I didn’t take a prep course, nor did I receive professional advising, but I did have to pay for the MCAT twice. I only took it once actually, but I didn’t consider that my legal name is actually misspelled on my license until it was too late to change the information without getting a refund — my fault, lesson learned.

It’s a good idea to purchase the MSAR

You can save money during the primary application by purchasing full access to the Medical School Admissions Registry (MSAR, it’s the best ~$25 you’ll ever spend). It has genuine data straight from the horses mouth, the schools themselves. By the MSAR when you’re planning your school selection list. You want to know what the lowest GPA and highest GPA Stanford accepted last year? Check the MSAR. Curious how many admitted students performed research? MSAR. The MSAR will also tell you things like the previous year’s: class size, interview/acceptance ratio, out-of-state vs in-state acceptance data, tuition, mission statement, links to housing and student clubs, it’s pretty useful to say the least when trying to find a program that fits you.

Be aware that some schools just automatically send you a secondary after your primary and haven’t actually checked or screened your application in any way.

You can also save a lot of money and anguish by seeing which school’s automatically send you a secondary and those who screen you first. I made sure to apply to some schools that didn’t screen (roll of the dice) and other schools who did screen me first (my canary in the cave). It worked out, I bought the MSAR after I paid for my primaries, so I used it to focus on what secondaries I should focus on when they started rolling in. I knew I made it past the initial score hurdles when I received secondaries from schools who screened first. I knew they already liked me by the time I was doing their secondaries, subsequently all three schools that I was accepted into right off the bat were schools that pre-screen their applicants primary to making you complete secondaries. It should be noted that I was also handed down a rejection by a pre-screening school. I was also invited for interviews to schools who didn’t pre-screen, but I’m actually waiting to hear back from several schools still. I believe focusing on schools that fit me, and schools that pre-screened saved me a lot of money.

Though, there is a benefit to not getting screened, you might land a good interview surprisingly. I won’t know my acceptance status of my top choice until January, but it was from a good program that didn’t screen; so rolling the dice is sometimes worth it.

If the school offers a hosting program sign up as soon as possible, it’s a pretty awesome experience and saves money. Notice I said “if”.

I’m not sure how but I literally had the best hosts in the world. My host in Boston set up the logistics of my stay from afar, all while being consumed by doctor stuff on his clerkship. Our schedules didn’t work out, but our phone conversations and outlook on being a physician told me more about the program than any tour could do. My other hosts in Michigan were so welcoming, accommodating, and forthright honest that I really started to wonder how one is reasonably supposed to select a medical school — along the way you meet great people, and you just want to stay there. They may be your future classmates, so learn from them what the program is like, the pros and cons, what the school considers important etc. And of course not fronting for room and board is pretty great on your wallet. It’s also pretty great because they can take a lot stress off of you on interview day by telling you how to actually get to your interview. Be sure to buy them a beer if possible because they just saved your life.

If you’re sticking in state then a lot the room and board problems won’t exist. Interestingly, Californians are rather competitive candidates out of state, but not that competitive in-state. Usually, states are pretty generous to their own, so a lot of people choose to save money with travel and tuition fees by applying in state.

Planes Trains and Automobiles

If you have to travel to other states like I did, then you’ll find websites that do rate comparisons to be pretty essential, personally I used Priceline for all of my flights, and I stuck with one carrier the whole time. I tried to buy multi-flight tickets, because it’s much cheaper than doing one trip at a time, for example my Boston-Michigan-Chicago trip, flying out of southern California, cost $805, compared to perhaps costing $400/500 each (early ticket prices). To save money I never checked bags (it costs about $25-$35 per bag, per flight), you can bring two carry-on’s: one must be stored in the bin above you, and one can fit under the seat in front of you. I found it was okay to fold my suit neatly as long as my hotel had an ironing board. The window for cheap tickets for a single round trip flight seems to be about 6 weeks. Sometimes you’ll take a smaller plane with inadequate bin space, and you’ll have to do some ‘last second’ bag check, it’s free though somewhat of a hassle. I never checked my bags because I’d be pretty screwed if the lost my suit and dress shoes, so it was like a suitcase full of gold to me. You can also check into your flight online, and send your boarding passes to your phone, this saves you a lot of headache.

Upon landing at my destination I needed to already have a idea of if I wanted or even needed a rental car. Cars give you an ability to control your fate in an unknown environment, but it’s just another expense to tack onto your bill, so if you can get around with buses, trains and an occasional taxi then you probably should just go with that. But, you’ll have to plan ahead, if it’s a $70 dollar cab ride from the airport to your hotel then you probably should just opt for the car in my opinion because it might be as low as $25-45 a day to rent it if you shop around.

In general, you’ll save a lot of money if you plan ahead and cut costs where you can, but do remember if you go too cheap you’ll be in a foul mood and possibly late to things.

Did you get accepted? GREAT! Now pay a deposit. You need to drop a refundable deposit for most schools, it’ll range in costs from $100 to $500 (ouch).

So the good news of spending several hundred dollars more is admittedly better than not getting offered anything at all. The bad news is that you’re paying deposits, and if you’re paying them mid-interview season then you’re probably going to be hurting because most deposits are due two weeks are less after you receive an offer of admission. For very early applicants an acceptance will roll in at the earliest October 15th (perhaps earlier for those who applied for the early decision process), so you’ll need to plan for deposit money in case you receive an early interview plus good news. The deposit are purely symbolic because you’ll get all the money back on May 15th, it prevents applicants from hoarding acceptances, and thus frees up space for those on the waiting list.

In the end, despite my frugal spending, and planning I was left with $1 dollar in my checking and about $2 dollars in my savings account. They say medical school is an investment, they aren’t kidding. But, at least my pre med days are over.

Update December 24th

So far I have received four US MD acceptances , and awaiting one more result in the beginning of January. So, now, with the power of foresight I’d say it was all worth it. Hang in there premeds.

Update April 16th

So, I was accepted into 5 schools (yay!), I was sent 8 interview invites, and declined 3 after the acceptances were rolling in and the money was rolling out. It seems that I am settled on Boston University School of Medicine. It was well worth the gamble!

Nothing risked, nothing gained.

You can follow my updates via RSS or follow/talk with me on https://twitter.com/doctorORbust